Citizens and sensors

Eight rules for using sensors to promote security and quality of life

Report

Downloads

The Dutch accept the use of sensors for safety and quality of life, but there are conditions. The acceptability of a sensor depends on the degree of safety and the type of living environment. This report, written at the request of the police, therefore presents eight rules for the use of sensors for safety and quality of life.

In the Netherlands, sensors, such as cameras or trackers that follow and record your movement, are increasingly being used to promote quality of life and safety:

- citizens and businesses own around 1.5 million security cameras;

- municipalities have more than 3,000 surveillance cameras;

- the police have around 500 to 1,000 surveillance cameras.

As new technology becomes smaller, more mobile, and cheaper, it can be installed more easily, such as with cameras in smartphones. Furthermore, the collection and processing of data is becoming easier, such as with smart algorithms in apps. This has created an extensive network of sensors that produce a large amount of data. This network consists not only of new sensors, but also of new actors and forms of supervision:

- citizens are monitored by the government and companies (surveillance);

- citizens use sensors to monitor each other (horizontal surveillance);

- citizens use sensors to monitor the government and companies (sousveillance).

In this report we outline various trends that show how supervision is changing:

- We are seeing more and more use of sensors and sensor data by the police.

- We see automation of core police activities such as witness tracking and enforcement through smart sensor technology.

- We see citizens, companies, and municipalities collecting more and more sensor data.

- We see new forms of cooperation between the police and other actors in society to use sensors for quality of life and safety.

- We see private parties that conduct their own investigation and enforcement with sensors and sensor data.

Which factors determine how citizens think about sensors?

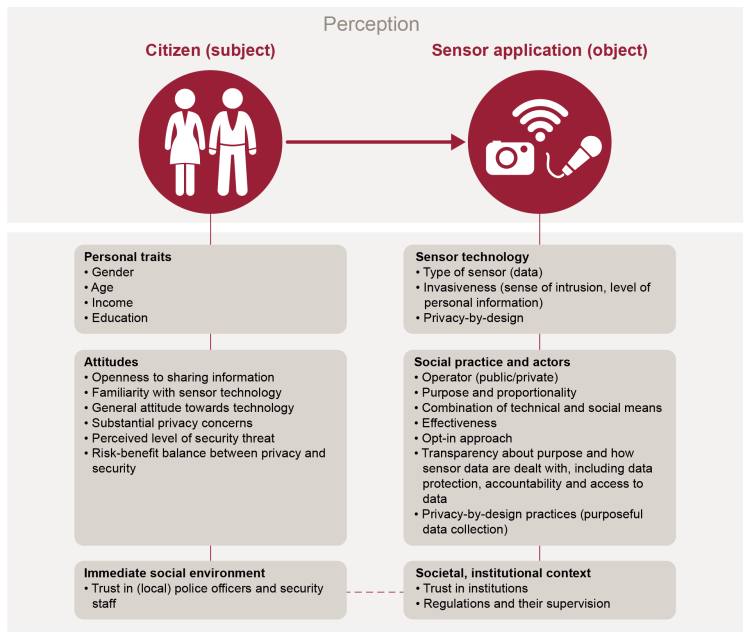

In order to gain insight into the opinion of citizens about the use of sensors for safety and quality of life, we developed a conceptual framework (see Figure 1). Here, we distinguish three dimensions of citizens (left-hand column, in bold) and three dimensions of sensor applications (right-hand column, in bold) that influence how citizens think about the use of sensors for quality of life and safety.

The literature shows that personal traits, general attitudes, and the immediate social environment play a role in informing the public’s opinions. For example, older people are more likely than younger people to accept sensor technologies. It also appears that men are more likely to consider the party using the sensor (such as the police or a private security firm) important, whereas for women it is the purpose of the investigation. Finally, having a positive attitude towards technology in general tends to boost a person’s confidence in sensors.

We also differentiate between three dimensions of sensor applications that influence the public’s opinion of sensors. To begin with, there is the technology itself, i.e. the type of sensor and the extent to which it incorporates privacy-by design principles. The next dimension is social practice and actors, referring to the context in which the technology is being used and the people or organisations involved. Finally, there is the societal and institutional context, for example legal regulations concerning camera surveillance or the level of public trust in the authorities. To find out more about what the Dutch public thinks of sensor technology, we organised various focus groups.

What does the Dutch public think about using sensors?

The picture that emerges from the focus groups is nuanced. It is impossible to talk about the acceptance of certain sensors or technologies without considering the context. People are neither for or against certain technologies, such as body cams or Wi-Fi trackers. Their opinion depends on:

- the features of the technology itself

- the purpose for which it is being used

- the effectiveness of the technology

- the type of crime for which the technology is employed, and

- the context in which it is applied (where, when, how, by whom).

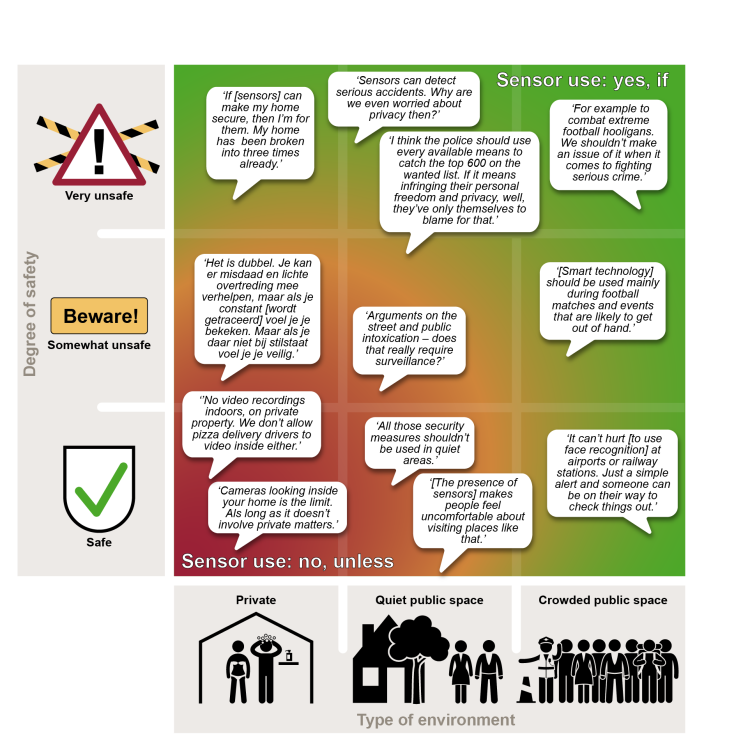

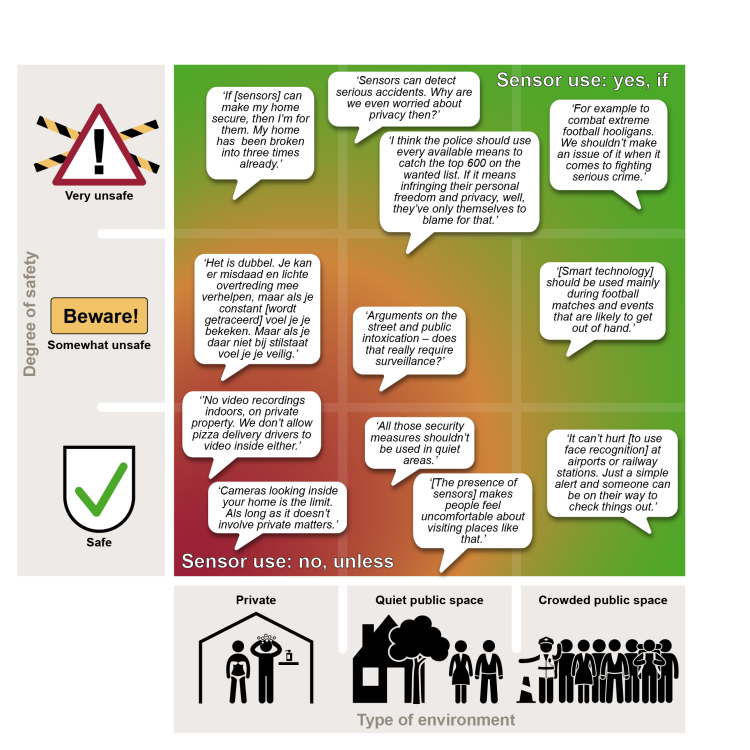

The focus group discussions revealed that two factors are particularly important: the setting in which sensor technology is used, and how safe people feel in that setting (see Figure 2).

We see that acceptance of sensors depends on the perceived level of safety: the more risk people perceive in a situation, the more they tolerate the use of sensors to improve security and quality of life.

Acceptance also depends on the setting: the use of sensors in private settings is less acceptable than their use in public places, especially in crowded situations.

On the one hand, then, people do approve of the use of sensors in very unsafe circumstances and crowded public places, but only if doing so meets a number of important criteria. On the other hand, people do not approve of using sensors in private homes or in quiet public places that feel safe or only slightly unsafe, unless doing so clearly improves security and quality of life and meets a number of important criteria, for example relating to privacy and personal freedom.

The focus groups revealed that values also guide people’s opinions. For example, the discussion about sensor technology use was often framed as a trade-off between security and privacy. At the same time, people clearly feel that a broader range of values should be considered when using sensors. In addition to security and privacy, these values include democratic rights, efficiency, effectiveness, innovativeness, transparency, quality of life and human contact.

Eight rules for using sensors

The police are expected to consider and in fact uphold the aforementioned public values when deploying sensors and sensor data. In reality, however, such values can be at odds with one another and the public therefore expects law enforcement to strike a healthy balance between disparate values, in consultation with the public. We have taken the results of our literature review and focus group research to come up with a set of rules governing the interpretation of these values in real-life situations. The rules are aimed specifically at law enforcement, but our study shows that the public would like other branches of government, businesses and fellow citizens to play by these rules as well.

- The police should use sensors in a way that inspires public trust.

- Provide the public with straightforward, transparent information about the use of sensors.

- Apply privacy-by-design principles.

- Citizens do not want the employment of sensors to lead to a reduced amount of presence of and contact with police officers.

- Citizens want the police to be both innovative and effective in the employment of sensors.

- The use of sensors may not lead to discrimination.

- Ensure personal freedom by restricting the use of sensors for security purposes to unsafe situations and crowded public places.

- The foregoing rules equally apply to cooperation between the police and other parties.

Preferred citation:

Snijders, D., M. Biesiot, G. Munnichs, R. van Est, met medewerking van S. van Ool en R. Akse (2019). Burgers en sensoren – Acht spelregels voor de inzet van sensoren voor veiligheid en leefbaarheid. Den Haag: Rathenau Instituut

It is about more than a trade-off between privacy and security

The discussion about sensor technology is often framed as a trade-off between security and privacy. The people participating in our focus groups were no different in this regard. At the same time, our study makes clear that, in the case of sensor applications, people value a broader array of underlying ideals. People expect law enforcement to strike a healthy balance between these disparate values, in consultation with the public. In addition to physical safety and privacy, these values include democratic rights, efficient and effective operations, innovativeness, transparency, quality of life, autonomy or personal freedom, and human contact.

Eight rules for using sensors

The police are expected to consider and in fact uphold the aforementioned public values when deploying sensors and sensor data. In reality, however, such values can be at odds with one another and the public therefore expects law enforcement to strike a healthy balance between disparate values, in consultation with the public. We have taken the results of our literature review and focus group research to come up with a set of rules governing the interpretation of these values in real-life situations. The rules are aimed specifically at law enforcement, but our study shows that the public would like other branches of government, businesses and fellow citizens to play by these rules as well.

- The police should use sensors in a way that inspires public trust.

- Provide the public with straightforward, transparent information about the use of sensors.

- Apply privacy-by-design principles.

- Citizens do not want the employment of sensors to lead to a reduced amount of presence of and contact with police officers.

- Citizens want the police to be both innovative and effective in the employment of sensors.

- The use of sensors may not lead to discrimination.

- Ensure personal freedom by restricting the use of sensors for security purposes to unsafe situations and crowded public places.

- The foregoing rules equally apply to cooperation between the police and other parties.

Citizens are not for or against a certain technology, such as bodycams or wifi trackers. This report shows that two factors are of particular importance: the type of living environment in which sensor technology is applied and the degree of safety that citizens experience.