Definitions and policy

This page is devoted to closer examination of the legal framework for valorisation in the Netherlands and the valorisation policy of the various organizations involved. We will start by considering the concept of valorisation, also referred to as impact or knowledge transfer or exchange, itself. Is there general agreement about its significance?

By Leonie van Drooge & Stefan de Jong | reading time 8 minutes | download pdf

Valorisation can be defined in many different ways

Different organizations define valorisation in different ways. Some stress its importance for economic activities, while others focus on such aspects as cooperation, relevance, impact and knowledge exchange. If we want to give an effective reply to people who ask what valorisation is precisely, we need a generally applicable definition.

But this is not easy to find when so many different ideas about the nature of valorisation are in circulation. This is surprising in a way, because the ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) and leading Dutch scientific organizations such as the Association of Dutch Universities (VSNU), the Vereniging Hogescholen (Association of Dutch Universities of Applied Science), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) share very similar views about the nature of valorisation. Basically:

- valorisation is a process;

- valorisation aims at enhancing societal impact in the widest sense of the term, including economic impact;

- valorisation is possible in all different disciplines;

- valorisation can occur in many different forms.

The ministry of Economic Affairs is the only one that takes a slightly different view, stressing the impact on industry in its definition.

Relevant legal provisions in the Netherlands

Valorisation or transfer of knowledge to society is among the duties of Dutch universities, universities of applied science and the various research institutes governed by NWO and KNAW. In many cases, this is a statutory duty. For example, Article 1.3 of the Higher Education and Research Act (Wet op het hoger onderwijs en wetenschappelijk onderzoek) [1], which describes the tasks of the Dutch institutions of higher education, includes the following passages concerning universities and universities of applied science:

- Universities have the tasks of providing academic education and performing scientific research. They shall in any case provide initial training in higher education, perform scientific research, provide training for scientific researchers or technological designers and ensure knowledge transfer to the benefit of society.

- Universities founded on a confessional or religious basis (…) shall ensure (…) knowledge transfer to the benefit of society.

- Universities of applied science (…) shall in any case ensure knowledge transfer to the benefits of society.

Article 3 of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research Act (Wet op de Nederlandse organisatie voor wetenschappelijk onderzoek) [2] includes the following description of one of NWO’s tasks: The organization shall promote the transfer of knowledge concerning the results of research initiated and stimulated by it to meet the needs of society. This refers to NWO’s role in financing scientific research.

There are fewer statutory provisions concerning the tasks of the research institutes governed by NWO and KNAW. Nevertheless, both organizations have formulated ambitions for these institutes. For example, NWO states on its website [3] that its institutes develop and disseminate knowledge and that they actively [seek] links with private and social partners. KNAW states [4] that it is its ambition to get its institutes to pay greater attention to knowledge utilization.

The ministry of Education, Culture and Science focuses on process and diversity

The Dutch government has adopted the following definition since 2009:5

Valorisation is the process of creating value from knowledge by making knowledge suitable and/or available for economic and/or societal use and translating that knowledge into competitive products, services, processes and entrepreneurial activity.

*The ministry of Education, Culture and Science has modified this definition slightly in recent years by deleting the word “competitive”. [6]

It follows from this definition that valorisation is a process, not a product like a patent, letter to the editor or treatment protocol. Furthermore, valorisation consists of activities aimed at the creation of value and making knowledge suitable or available for use, such as translating knowledge, applying it or being inspired by it.

Another important aspect of valorisation is that it must be based on interaction. Research institutes need to collaborate or team up with partners, because at least two parties are needed for the joint production of knowledge or the exchange or transfer of knowledge. The following statement was made in an explanatory note on the above definition of valorisation [7]:

Valorisation is a complex and iterative process in which interaction between research institutes, companies, NGO’s and social institutions is important at all stages, including that of knowledge development.

The above definition states that economic and/or societal use is the objective of valorisation, not that it should lead to higher earnings for universities, or that the knowledge generated should only benefit industry and commerce.

Nevertheless, it is these aspects of valorisation that receive almost all the attention, while the societal aspect remains rather abstract and unclear for many people. This is why the ministry of Education, Culture and Science included the following statement in its Vision of Science in 2025 [8]: We would like to emphasize once more at this point that we take a very broad view of the concept of valorisation. This includes not only the economic utilization of knowledge but also the use of knowledge to solve societal problems or to contribute to societal debate.

Is scientific communication part of valorisation? The minister of Education, Culture and Science [9] makes a distinction between scientific communication and valorisation, seeing them as two different aspects of universities’ statutory duty to ensure knowledge transfer to society.

The ministry of Economic Affairs stresses the impact on industry

The ministry of Education, Culture and Science is not the only Dutch government department to concern itself with valorisation. The ministry of Economic Affairs also considers this to be an important topic, and the two ministries work together in this field. However, the attitude of the ministry of Economic Affairs towards valorisation is coloured by its main roles, which include promotion of the interests of Dutch commerce and industry, the knowledge economy, entrepreneurship training and public-private partnerships.

According to its own website, the ministry of Economic Affairs does its best to create an excellent entrepreneurial climate in the Netherlands, and wishes to encourage cooperation between researchers and entrepreneurs [10]. This emphasis on the importance of knowledge for Dutch industry and commerce is reflected in the ministry’s valorisation policy. Both in the ministry’s policy for encouraging the pursuit of a climate of excellence in the top sectors of the Dutch economy and in its valorisation programme, the main stress is placed on encouraging cooperation between research institutes and companies, on transferring knowledge and innovations to companies and promoting the growth of the knowledge economy. In this way, the ministry of Economic Affairs concentrates on a subset of the activities involved in the valorisation process, namely those that serve the interests of industry and commerce.

In fact, Economic Affairs was not alone in adopting such a narrow definition of valorisation. The former State Secretary of Education, Culture and Science, Halbe Zijlstra, also used to stress the importance of entrepreneurship and the economic aspects of valorisation through his well-known motto: “Skills and know-how mean more cash in the till” (“kennis-kunde-kassa”).

Surprisingly enough, many researchers also refer to this narrow definition of valorisation rather than the broad definition adopted by the Dutch government. This may be one of the reasons for the inclusion in the Vision of Science in 2025 of the passage which we have already cited above: We would like to emphasize once more at this point that we take a very broad view of the concept of valorisation.

Dutch universities are developing indicators

The ministry of Education, Culture and Science reached agreement in 2012 with the umbrella organizations VSNU and Vereniging Hogescholen (Association of Dutch Universities of Applied Science) that Dutch universities and universities of applied science would develop valorisation indicators in order to monitor the progress made in this field by individual universities or universities of applied science. This agreement was necessary because it was not clear at that time what was going on in this field, what valorisation really meant and what was being achieved.

The VSNU submitted an assessment framework to the ministry in 2013, while the Vereniging Hogescholen submitted a toolkit in the same year. Together, these two models formed the first step towards a comprehensive set of valorisation indicators. It was further agreed that these two umbrella organizations would work together with their member organizations to fill in the gaps in these models so as to deliver a complete set of indicators – one for the universities and one for the universities of applied science – by 2016.

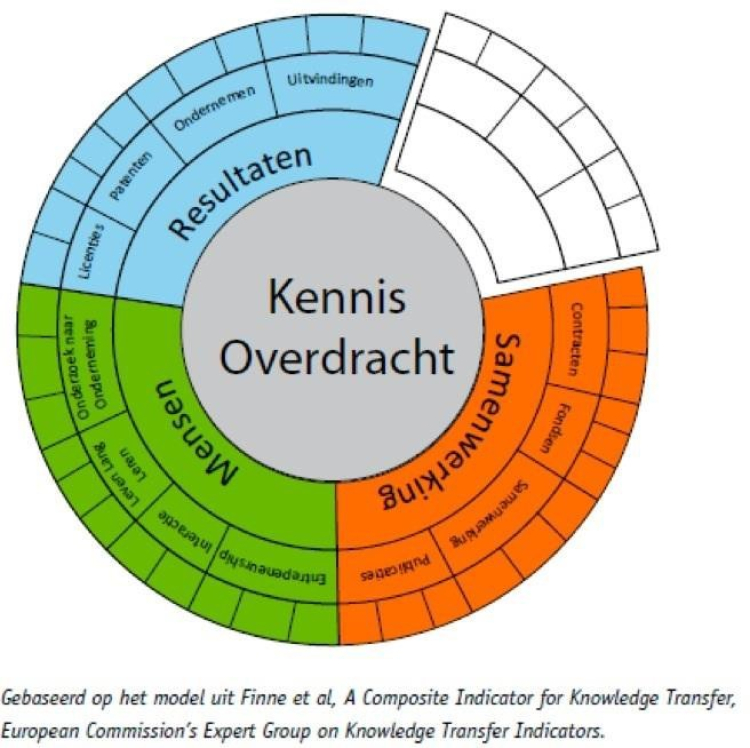

While there are differences between the above-mentioned framework and the toolkit, they also resemble one another in certain respects. The main thing is that both of them are based on the idea, in line with the definition used by the Dutch government, that valorisation is a process. As a result, it cannot be monitored only by looking at results; it is also necessary to consider process parameters during or even before research, such as cooperation with external partners, financing by third parties or exchange of staff. Another common characteristic of both approaches is their flexibility: both umbrella organizations state that their models are based on use of a selection menu. They do not expect all research institutes to achieve a high score on all indicators, or that all indicators will be equally relevant to all research institutes.

It should be noted in this connection that the indicators in these models are defined at the level of the university or university of applied science. In other words, they refer to matters organized at the level of the institution as a whole, such as HR policy or relations with other organizations, for which the individual research groups within the institution are not responsible. It is not clear at the moment whether adding up all the relevant indicators for individual research projects would lead to an informative, representative picture of valorisation at the level of the university or university of applied science as a whole.

NWO stresses the importance of knowledge utilization

The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) has many different research financing schemes, ranging from the Applied Research (Praktijkgericht Onderzoek SIA) programme for universities of applied science and the Force of Gravity (Zwaartekracht) programme for influential innovative research by consortia of top-class researchers to investment schemes to permit the acquisition of large pieces of equipment and research grants for individual excellent researchers. A number of these NWO financing schemes focus on valorisation, such as the Responsible

Innovation (Maatschappelijk Verantwoord Innoveren) programme and the programmes relating to the Dutch government’s “top sectors” policy. There are also programmes which, while not explicitly aimed at promoting better knowledge utilization, have this as one of their criteria – in particular the Veni, Vidi and Vici grants for talented, creative researchers set up within the framework of the Innovational Research Incentive Scheme.

NWO defines knowledge utilisation as the process promoting the use of scientific knowledge outside the scientific world and by other scientific disciplines. NWO regards the use of knowledge within the scientific field, but outside one’s own discipline, as a form of knowledge utilisation too. It is the only Dutch organisation to explicitly formulate this type of knowledge utilisation.

NWO states that knowledge utilisation often demands interaction between the researcher and the intended user of the knowledge in question. This interaction may occur at any stage of the research, from the formulation of the initial research question to dissemination of the results. By pointing this out, NWO indicates its agreement with the idea that valorisation, or knowledge utilisation, is a process, and that it does not only occur towards the end of a research project. NWO asks applicants for research grants to state whether potential users are involved in the research process, and if so how and when they are involved. The applicant should also mention the expected benefits of the research for society.

Each of the sectors of NWO adds its own explanatory comments to the basic concept of knowledge utilisation, to reflect the view that the precise meaning of knowledge utilisation depends on the discipline involved.

SEP focuses on societal relevance

The Standard Evaluation Protocol (SEP) developed by VSNU, NWO and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), lays down the criteria used for the retrospective or ex post evaluation, every six years, of the research performed in the various departments and research institutes of Dutch universities, and in the various research institutes governed by NWO and KNAW. VSNU, NWO and KNAW publish a new SEP protocol every six years. The latest is SEP 2015-2021 [12].

Societal relevance (valorisation) has long been included as a criterion in the SEP, but the interpretation of this criterion has been found to give rise to many questions in practice. SEP 2015- 2021 does not go into detail about relevance to society, as it is currently referred to. In connection with the quality, scale and relevance of the contributions made to specific economic, social or cultural audiences, of advisory reports for policy-makers, of contributions to public debate and the like, the protocol simply states that the contributions should be made to questions, or issues or practices that are relevant for the research unit.

SEP 2015-2021 includes a table that is clearly inspired by a number of KNAW reports (see the section on the KNAW below). This Table D1 mentions two aspects of quality: research quality and relevance to society. These two aspects correspond to two of the three criteria in the SEP. Each of these aspects is assigned three evaluation dimensions: products, use and recognition. A number of example indicators are given in the table.

The SEP does not include any clear definition of valorisation or societal relevance, but it is clear reading between the lines that the three crucial elements of valorisation apply here too. The nature of valorisation as a process is reflected by several of the example indicators, while the explanatory notes and the examples given in the SEP refer to not only the economic but also the societal and even the cultural use of research results. Furthermore, the SEP intentionally avoids including an exhaustive list of indicators in Table D1; instead, users are requested to add further indicators that are appropriate to the research in question.

The SEP also asks for a narrative description of the societal relevance or impact of the research in question. The indicators from Table D1 are intended to support this narrative. A description of the approach taken by the research group is crucial in this context. The idea underlying this question is that the impact or relevance of the research does not come about automatically. It might appear to do so (“we happened to receive a request”), but such requests are usually the result of preparatory work or contacts. The need to write a narrative description may help researchers to become aware of the often initially subconscious active role they played in ensuring that their research would have an impact.

Valorisation is a very wide field – how can you evaluate it?

The broad definition of valorisation used here has far-reaching consequences. It provides an excellent opportunity for researchers to determine what valorisation means for their discipline or in their research institute. On the other hand, it does lead to a great many questions, both among those who are evaluating the research and among the researchers and the research groups being evaluated.

Fortunately, there are answers to these questions. In the first place, few if any indicators are specified in the VSNU proposal, in the information about NWO’s Innovational Research Incentive Scheme or in the SEP. Instead, users are explicitly invited to indicate what valorisation means in their specific situation. They are free to determine which indicators are applicable to their particular case, and can include qualitative indicators as well as quantitative ones.

Furthermore, there have been various projects in the Netherlands aimed at evaluating valorisation, impact or the societal quality of research [13]. The KNAW has produced a number of reports on research assessment, which form the basis of the current SEP. These reports also do not give exhaustive lists of indicators – not even short lists of the only right indicators. They do however provide extensive explanatory notes on social quality.

These KNAW reports are largely based on the results of the Dutch ERiC (Evaluating Research in Context) project. The context in question is a wide one, covering the discipline involved, the organisation responsible for the research and other parties taking part in the research. These details are highly relevant, because it makes a big difference whether the research is monodisciplinary or interdisciplinary, whether it is carried out in a university of technology or a mission-driven social science institute, and whether it is carried out with and for scientific peers or in a consortium that also includes societal and industrial or commercial players.

In line with this, the first questions asked in the ERiC project are: What is the objective of the study, and what is the context? The answer to these questions determines whether the evaluation of the research can be based exclusively on traditional quality indicators such as scientific publications and citations, or whether it is also necessary to include other aspects, such as the nature of the involvement of societal partners.

KNAW develops quality criteria in specific sectors

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) is the forum, conscience and voice of Dutch science, and advises the Dutch government on issues of importance to science in the Netherlands. The KNAW has published three advisory reports on research evaluation in recent years, dealing with technical sciences (with special reference to their design and constructional aspects), the humanities and the social sciences. These reports were produced in response to the need for more specific, discipline-oriented quality criteria in these disciplines. Each report contained a brief proposal concerning research evaluation criteria.

Although each of these reports has a different structure, there are many similarities between the approaches taken. The intention in each case was definitely not to develop valorisation indicators, but to formulate appropriate quality criteria for scientific research. The Academy members always came to the conclusion that there are two relevant aspects of quality: the scientific and the societal.

The main stress in these reports – particularly in the proposals for the humanities and the social sciences – seems to be on the use to which research results are put and their impact on external target groups rather than on the cooperation between the various parties involved. However, reading between the lines it may be concluded that a reference to cooperation with social partners is hidden in the quality criteria “products for external target groups” and “use of output by society”.

These reports are also in line with the definition of valorisation adopted by the Dutch government. The publication of separate reports for different disciplines reflects the conviction that different valorisation approaches need to be taken or can be taken in different disciplines. The insight that valorisation is a process is not stated explicitly in two of the three KNAW reports, but is implicitly present. The proposed quality criteria reflect a broad view of valorisation, stressing its societal as well as its economic aspect.

In conclusion

Many people still recall the memorable motto “Skills and know-how mean more cash in the till” coined by Halbe Zijlstra, State Secretary in the Dutch cabinet from 2010 to 2012. Nevertheless, the Dutch government, in particular the ministry of Education, Culture and Science, have been using a much wider definition of valorisation for more than a decade now.

Societal impact is just as important as economic impact. Valorisation is an interactive process and not just a simple kind of linear leapfrog. It aims at both economic and societal impact, and can be tailored for use in each discipline.

Each of the Dutch umbrella organizations Vereniging Hogescholen, VSNU, NWO and KNAW takes its own slightly different view of valorisation – or knowledge utilisation, or relevance to society, whichever name they choose to give to this concept. But in fact the resemblances between their views are greater than the differences. What matters is not just that skills and know-how lead to economic benefits, but that research can have different kinds of impact, achieved via an appropriate process that will differ from one discipline to another. It follows that it is up to the researchers themselves to determine what kind of impact they are aiming at, and what indicators they need to evaluate their results.

References

[1] http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0005682/volledig/geldigheidsdatum_10-02-2015#Hoofdstuk13

[2] http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0004191/geldigheidsdatum_10-02-2015

[3] http://www.nwo.nl/over-nwo/wat+doet+nwo/instituten

[4] https://www.knaw.nl/nl/de-knaw/beleid

[5] Nederland Ondernemend Innovatieland (2009). Van voornemens naar voorsprong: Kennis moet circuleren. Den Haag: Interdepartementale Programmadirectie Kennis en Innovatie.

[6] http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/bestanden/documenten-en-publicaties/convenanten/2011/12/12/hoofdlijnenakkoord-ocw-vsnu/hoofdlijnenakkoord-ocw-vsnu.pdf

[7] Leonie van Drooge, Rens Vandeberg et al. Waardevol: Indicatoren voor Valorisatie. Den Haag, Rathenau Instituut, 2011.

[8] Ministerie van OCW (2014). Wetenschapsvisie 2025. Den Haag: Ministerie OCW. P. 40

[9] Minister van OCW (27 januari 2005). Valorisatie van onderzoek als taak van de universiteiten. Brief aan de voorzitters van de Colleges van Bestuur van de universiteiten. OWB/AI/04-57055

[10] http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/ez geraadpleegd op 11 maart 2015

[11] VSNU (2013): Een Raamwerk Valorisatie-indicatoren. Den Haag: VSNU

[13] ERiC (2010) Handreiking Evaluatie van maatschappelijke relevantie van wetenschappelijk onderzoek Den Haag: Evaluating Research in Context. Zie ook: Leonie van Drooge, Rens Vandeberg et al (2011) Waardevol: Indicatoren voor Valorisatie. Den Haag, Rathenau Instituut.

Colofon

This e-publication is an initiative of the Rathenau Instituut and part of the projects 'Valorisation as knowledge process' and 'Valorisation in the social sciences and humanities.'

Authors: Leonie van Drooge and Stefan de Jong

Web-design: Herbert Boland

Images: through the interviewees and Wikimedia

Please cite as: Leonie van Drooge and Stefan de Jong. Valorisatie: onderzoekers dan al veel meer dan ze denken - e-publicatie met voorbeelden en handvatten om zelf valorisatie te organiseren. The Hague: Rathenau Instituut, 2015.