Harmful Behaviour Online

Photo: Shutterstock

But what kind of behaviour are we talking about? How prevalent is it? And what can the Dutch government do about it? At the request of the Research and Documentation Centre for the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security (WODC), the Rathenau Instituut has studied harmful and immoral behaviour online

Downloads

Downloads

-

Download Harmful Behaviour Online

Report

-

Download English summary Online Ontspoord

Summary (English)

Research questions

The internet has certain properties that tend to derail online behaviour. A person who would never insult a passer-by on the street may have no trouble doing so on Twitter. Someone who would never steal from the local supermarket may feel less inhibited about stealing credit card information online. In their book Evil Online (2018), Dean Cocking and Jeroen van den Hoven describe the internet as an environment in which harmful and immoral behaviour is inspired, facilitated and encouraged. This book made the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security wonder what the status of such behaviour is in the Netherlands.

The Ministry’s Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) asked the Rathenau Instituut to answer the following research question: What is the nature and scale of harmful and immoral behaviour online in the Netherlands, what are the underlying mechanisms and causes, and what options for action are available to the Ministry, and the government as a whole, for limiting harmful and immoral behaviour online?

Our report addresses online behaviour that takes place in a moral twilight zone, and in which the government is currently hesitant to act. We looked at online behaviour that can be designated as harmful and/or immoral. This behaviour is harmful not only to individuals but also to larger groups or society as a whole. Some of the behaviours that we discuss in this study violate certain fundamental rights and laws and are therefore unlawful or illegal. Yet it turns out that it is much more difficult for people to judge whether something is acceptable in an online environment. The online world is not necessarily more lawless or more of a free-for-all than the offline world, but it is more easily experienced as such.

In this report, the Rathenau Instituut uses a taxonomy to present a unique overview of harmful and immoral online behaviour in the Netherlands. This taxonomy can serve as a framework for a coordinated approach by the national government, in collaboration with the business community and stakeholders in civil society. A further aim is to contribute to the societal debate on what constitutes desirable and permissible behaviour online. We know that moral standards are subject to change and that public debate about these standards is necessary.

Approach

The report addresses the following sub-questions:

- What is the taxonomy of online behaviours and online phenomena that can be harmful to individuals or groups, and thus affect the moral fabric of society?

- What is the nature of these problematic behaviours and phenomena in the Netherlands?

- What is the scale of problematic behaviours and phenomena in the Netherlands, in terms of stakeholders, victims and damage to society?

- How are these problematic behaviours and phenomena, and the resulting damage to society, linked to the operation, underlying mechanisms and design of the online environment? In other words: how does the online world act as a facilitator and catalyst for harmful statements and behaviour on the internet and social media?

- What options for action have already been developed, nationally and internationally, for limiting harmful and immoral behaviour online and the societal damage it causes, and what lessons can be learned from them?

- What options for action does the Dutch government have?

To answer these sub-questions, we combined the following methods: literature review, interviews, workshops and meetings with experts from the fields of policymaking, professional practice and scholarship. A total of 56 such experts contributed to the study.

Summary

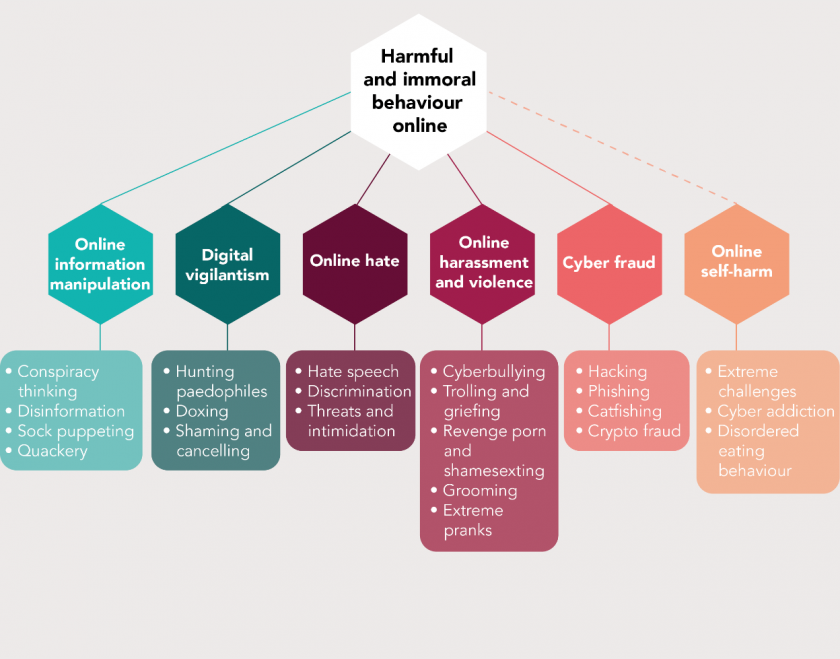

This study is the first to map all aspects of harmful and immoral behaviour online in the Netherlands. The Rathenau Instituut developed a taxonomy of six categories of harmful and immoral behaviour online, listing 22 different phenomena that all internet users in the Netherlands may encounter sooner or later.

Taxonomy of harmful and immoral behaviour online

The harmful behaviour listed in this taxonomy can severely impact individuals, groups and society as a whole. It can range from a teenage girl starving herself because she joins an extreme challenge with other adolescents or female journalists and scientists being discouraged from speaking out online in fear of harassment, to societal disruption due to the spread of conspiracy theories and disinformation.

Interviews with experts and the literature on the nature and scale of the phenomena listed in the taxonomy make clear that all Dutch people run the risk of becoming involved in this behaviour as a victim, perpetrator or bystander. Anyone can be affected by the harmful and immoral behaviour outlined in this report. However, for certain phenomena, some groups are more at risk than others, depending on their age, gender, race, sexual orientation, religious beliefs or level of education. It is difficult to generalise based on the available data.

The study shows that, to date, accurate definitions and systematic measurements are lacking for various phenomena. It is not useful to try to determine which phenomenon is the most worrying, as this depends on the criteria chosen: the number of victims, the severity of the harm, or the possible harm in the future. We conclude that all phenomena are worrisome in their own way, for society as a whole, for individuals or for groups of individuals.

Mechanisms

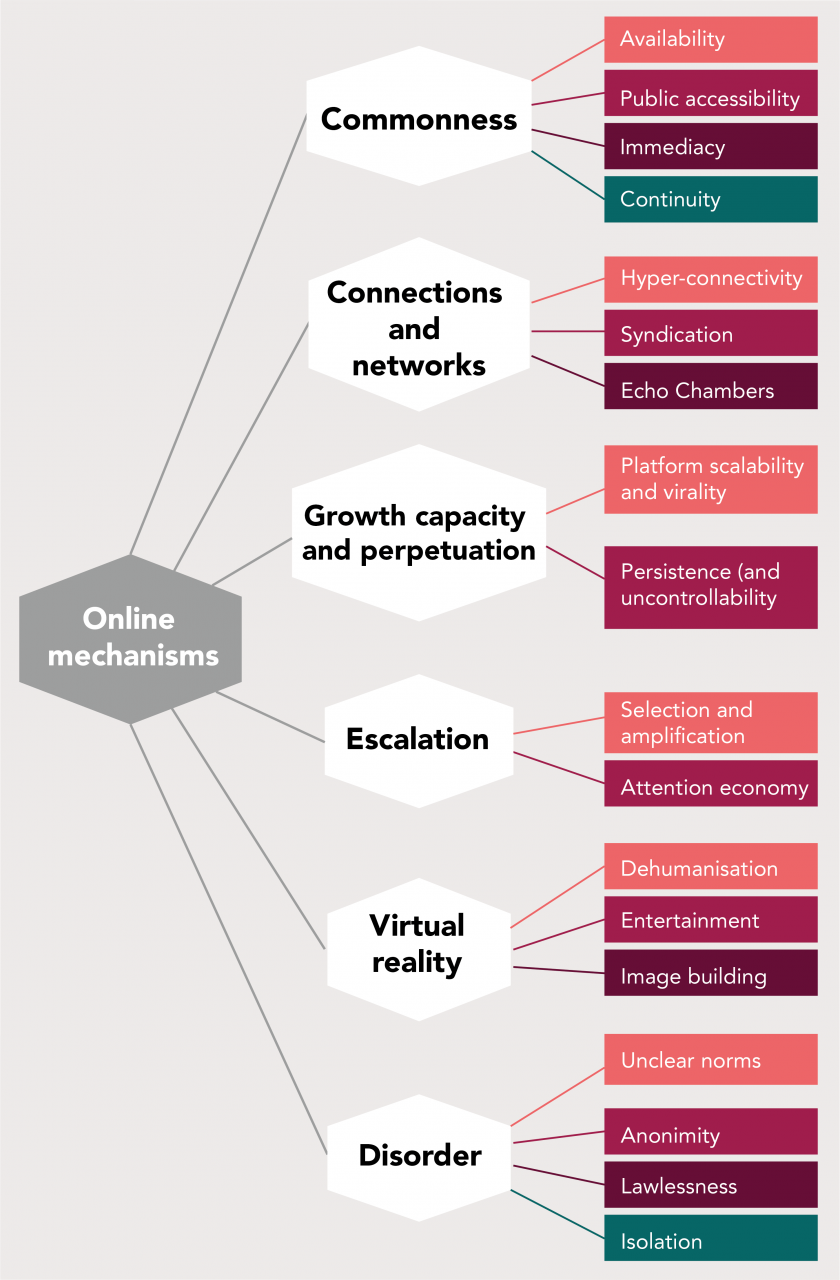

Certain mechanisms of the internet’s online environment influence human behaviour. These online mechanisms may cause people to deal with values and rules differently online than offline. Besides the mechanisms of the internet, many other factors influence human behaviour, including social, psychological, cultural and economic ones. All these factors play a role in the development of harmful and immoral behaviour online. This report focuses on mechanisms characteristic of the internet.

The study identified a total of 18 online properties and mechanisms that play a role in inspiring, facilitating and driving harmful and immoral behaviour online: 1) availability, 2) public accessibility, 3) immediacy, 4) continuity, 5) hyper-connectivity, 6) syndication, 7) echo chambers, 8) platform scalability and virality, 9) persistence (and uncontrollability), 10) selection and amplification, 11) attention economy, 12) dehumanisation, 13) entertainment, 14) image building, 15) unclear norms, 16) anonymity, 17) (apparent) lawlessness, 18) isolation. These mechanisms are grouped under six descriptive characteristics of the internet:

- Commonness

- Connections and networks

- Growth capacity and perpetuation

- Escalation

- Virtual reality

- Disorder

An overview of all mechanisms and their classification can be found in Figure 2 below.

The case studies in this report illustrate that the same mechanisms can play a role in very different phenomena, and that the mechanisms occur in combination. For example, syndication (the ease of finding like-minded people online) and virality (rapid, uncontrollable distribution of content online) play a role in the online shaming case, the disinformation case and the disturbed eating behaviour case. Intervening in the mechanisms, such as requiring transparency about the recommendation algorithms for online content or lifting the anonymity of internet users in certain environments, makes sense in preventing or reducing harmful and immoral behaviour online. But such interventions require careful consideration and societal debate. After all, the mechanisms of the internet can also lead to socially desirable behaviour and social merits. Anonymity online, for example, enables whistle-blowers to report societal malpractices. Intervening in these mechanisms may also limit or nullify these positive effects.

Options for action

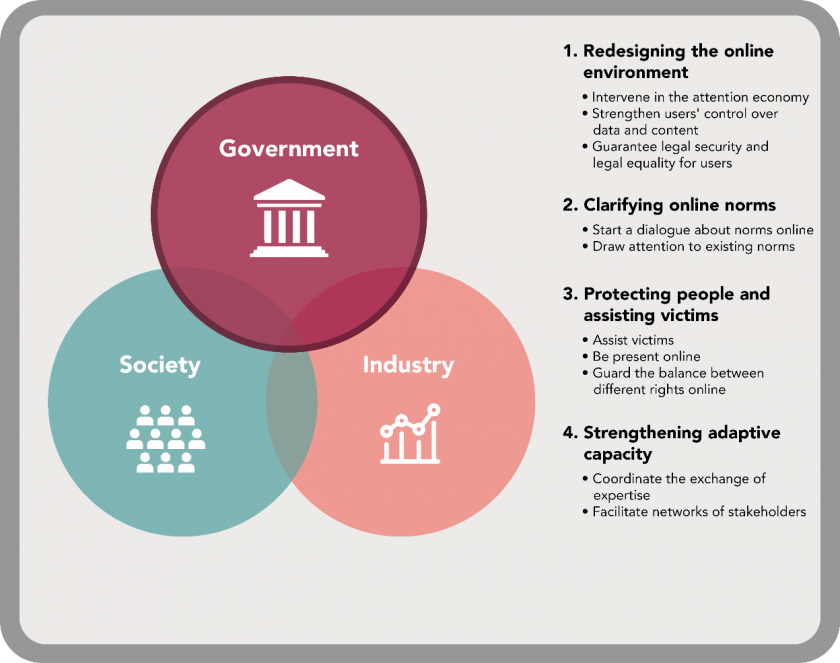

So far, the internet has been a domain of self-regulation and self-reliance, where the government has taken no responsibility for oversight and users have managed by themselves. However, our study shows that fundamental rights are at stake; citizens are insufficiently protected on the internet. Businesses, civil society organisations and citizens need an active government to counter harmful and immoral behaviour online, and to promote socially desirable behaviour online.

This report provides an overview of existing measures that governments, businesses, social workers and others have already taken to tackle harmful behaviour online. The overview reveals which interventions already work and seem promising when it comes to reducing or preventing harmful and immoral behaviour online. But it also reveals the shortcomings and where additional interventions are needed. The most important observation is that many of the current initiatives are mainly reactive in nature. They are aimed mainly at combating the symptoms of harmful and immoral behaviour rather than at the underlying mechanisms. In this respect, we see differences between various stakeholders. Governments and large platform companies in particular have not been very proactive. In the case of platform companies, this is not surprising. After all, tinkering with mechanisms means choosing an alternative form of platform design. This results in uncertainties about business models, and because companies operate in a competitive market, it is primarily other, small businesses and stakeholders that are experimenting with alternative forms of design.

Our analysis of existing measures shows that governments mainly take action when behaviours get out of hand and, therefore, need to be restrained. Up to now, their interventions have mainly been reactive. The overview of online mechanisms in this report can help governments and other stakeholders to be more proactive.

We introduce a strategic agenda for the Dutch government based on interviews and discussions with experts in the fields of policymaking, scholarship and professional practice, a review of academic and journalistic sources and policy documents, and the expertise gained by the Rathenau Instituut in previous research and analysis. In this agenda, we identify four themes in which the Dutch government can cooperate with stakeholders from industry and society to play a guiding, coordinating and facilitating role in tackling harmful and immoral online behaviour and promoting a safe online environment.

The first theme – Redesigning the online environment – contains options for the Dutch government to address the online mechanisms that contribute to harmful and immoral behaviour online. For example, the report makes a number of suggestions to intervene in the online attention economy.

The second theme – Clarifying online norms – deals with the role of the Dutch government, industry and society in renewing the social agreements on norms and values online. The options for action under this theme are intended to bring about broader awareness and understanding in society at large of harmful and immoral behaviour online.

The third theme – Protecting people and assisting victims – contains suggestions for the Dutch government, law enforcement and executive agencies to better respond to the phenomena of harmful and immoral behaviour online and the damage they cause. For example, we make a number of suggestions for the government to be more visible and present online.

The fourth theme – Strengthening adaptive capacity – offers suggestions for the Dutch government to gain and maintain a grip on harmful and immoral online behaviour, which is constantly changing. These options for action are aimed at future-proofing the strategic agenda.