Mission-driven innovation policy: what, how, why?

There's a new term in the Dutch field of research and innovation: 'mission-driven innovation policy'. But what exactly is that? Is it a logical step in the history of innovation policy? (spoiler: yes) And why do science, politics, business and civil society organisations need to work together? An article for anyone who wants to know more about the new buzzword and why the Rathenau Instituut is researching it.

It's July 13, 2018. Minister Wiebes and State Secretary Keijzer, both from Economic Affairs and Climate, present their implementation of the innovation policy announced in the coalition agreement. From now on, according to the letter to parliament, innovation policy must focus on four major societal themes:

- energy transition and sustainability;

- agriculture, water and food;

- health and care;

- safety.

In order to tackle these challenges, innovation policy with clear missions is needed.

Different kind of missions

The government is clearly inspired by leading missions from the past. Think of the Delta Works that had to protect the Netherlands from the rising water and the American Apollo space programme that wanted to have a man on the moon within ten years. These missions from the past, however, were mainly technically complicated. The current themes are much more complex and therefore require different kind of missions.

More cooperation

On 26 April 2019, State Secretary Keijzer presented an explanation of the innovation policy. A large number of parties must work together on each theme. These will not only be the usual suspects such as knowledge institutions, companies, research funders, and ministries. No, the government also sees an important role for start-ups, regional authorities and citizens' organisations, for example.

The idea is that the usual way in which we organise research and innovation in the Netherlands will not suffice for the major social themes. Until now, researchers in the Netherlands have mostly worked in disciplinary or public-private projects and programmes. Although this approach has yielded scientifically impressive successes and creates economic opportunities, in order to contribute to transitions the knowledge ecosystem has to change direction. This includes collaboration between scientists, governments, and social parties.

The collaborating parties must lay down their plans in so-called Knowledge and Innovation Agendas (Kennis- en Innovatieagenda’s) or KIAs. Such agendas were also used in previous top sector policy. An example of a new KIA is the one about agriculture, water and food. One of the missions will be about the transition to a circular agrofood system.

Mission-driven innovation policy to accelerate transitions

The government is therefore choosing a new strategy to speed up transitions. The associated term is mission-driven innovation policy. The term is new, but the strategy does not come out of the blue. The emergence of this approach fits in with a broader development in thinking about innovations.

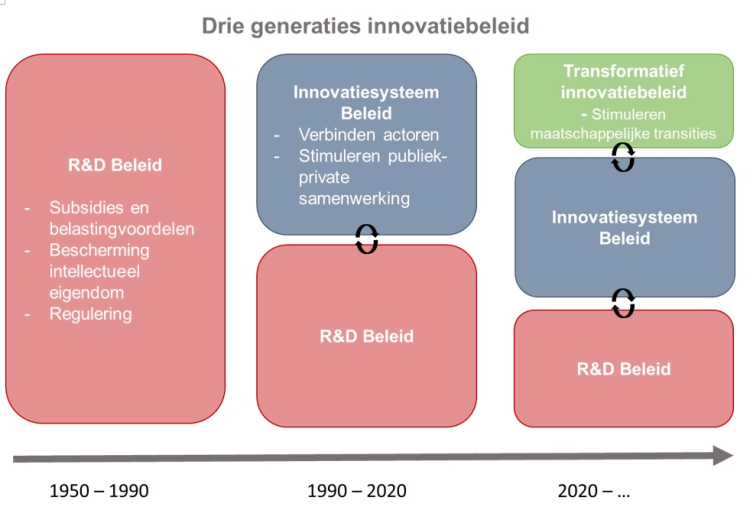

If you think of innovation policy as a long drink glass, then that glass in the 1950s-1990s was mainly filled with policies to seduce companies. In the period 1990-2020 the policy became a mix of one part attracting companies and one part stimulating cooperation. From 2020 onwards, the cocktail consists of three parts: attract companies, stimulate cooperation, accelerate transitions. Incidentally, this comparison with the long drink glass is not about money. Over the years, the government has started to spend more on innovation.

The Netherlands and Europe

The new mission-driven innovation strategy of the Netherlands is similar to that of the European Union. An important part of European research only receives funding to contribute to societal transformations. Horizon Europe, for example, the forthcoming European framework programme for research and innovation, includes a special section for societal missions. While the Netherlands is deploying 24 missions within four social themes, the European Union is deploying six clusters. The European clusters and the Dutch themes overlap. One of the European clusters, for example, is 'soil health and food'. This can be compared to the Dutch theme 'agriculture, water and food'.

Incidentally, there is sometimes confusion about the term mission. For example, a distinction is made between transformer missions and accelerator missions. Transformer missions, then, focus on transitions. Accelerator missions are intended for technological developments. For simplicity, this article uses the umbrella term 'mission'.

How do you bring groups together?

A major challenge for the government is how to organise governance and the execution of the missions. Recycling agriculture, for example, is a fine ideal on which many parties want to work, but how do you bring researchers from different disciplines and knowledge institutes into contact with farmers, supermarkets and consumers to jointly develop the necessary knowledge and innovations? And what roles should each of them play?

Co-creation

One way of integrating the social embedding of innovation into the research and innovation process is cocreation. Cocreation is actually a nice word for collaboration. It means that in addition to researchers and technology developers, end users, professionals, companies, governments, regulators, citizens and/or social parties are given an active role in putting innovative solutions on the agenda and co-developing them that are practically applicable and contribute to the mission.

Encouraging collaboration

Back to the question: how do you bring groups together? The government tries to encourage that cooperation. It does so, for example, by imposing conditions on the content of the innovation agendas, on the partners and on the form of collaboration. We will explain briefly below:

- Content of research and innovation agendas

A broad focus on innovation in which the social embedding is co-developed in the research and innovation process. - Partners in consortia

Not only scientists, but also non-scientists with knowledge and experience relevant to the societal embedding of innovation. - Cooperation methods

Special attention for transdisciplinary or cross-sector collaboration in research and innovation.

Social embedding

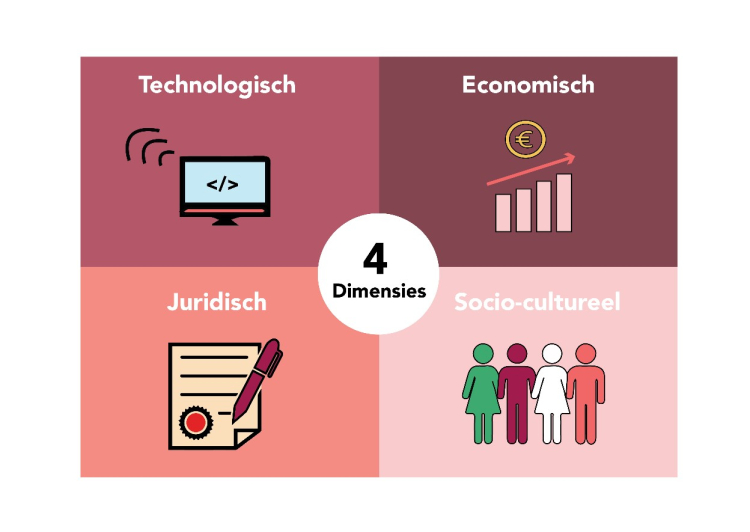

One point related to cooperation is the embedding of the innovations. An innovation can only successfully contribute to a transition if it becomes socially embedded. This means that innovation with a view to transitions requires much more than the development and application of a new technology. In the Rathenau report Voorbij lokaal enthousiasme: lessen voor de opschaling van living labs (Van den Broek et al, 2020) We distinguish four important dimensions for the social embedding of innovations. Namely, the technological dimension, the economic dimension, the legal dimension and the socio-cultural dimension.

The government can regulate any of these dimensions. If we take the circular agrofood system, for example, a technological dimension could be a competition for innovative solutions. An economic dimension is a lower VAT rate for vegetable food. The legal dimension then includes, for example, laws and regulations that impede the import of foreign proteins. And an intervention around the socio-cultural dimension (and also around the economic dimension) would be if the government only offered vegetarian products in company restaurants and at social gatherings.

An innovation can only successfully contribute to a transition if it becomes socially embedded.

Rathenau Instituut investigates three points of interest

Well, the above is a long introduction to the government's new mission-driven innovation policy. But what does that have to do with the Rathenau Instituut? It's quite simple. The Rathenau Instituut stimulates public and political opinion formation about the social aspects of science and technology. We conduct research and organise the debate on science, innovation and new technologies. And since mission-driven innovation policy is a new fate for the tribe of science and technology, it forms a research field for the Rathenau Instituut.

In a new project, the Rathenau Instituut is investigating three main points of focus of the mission-driven innovation policy:

- the level of democracy;

- the effectiveness;

- the regulation.

All in all, mission-driven innovation policy is a logical step in the history of innovation policy. Especially in view of the societal challenges that the government wants to tackle. In the coming period, the Rathenau Instituut will provide knowledge on how this new mission-driven innovation policy can be implemented.