Digitalisation informed by public values

Public wellbeing has improved considerably since the Industrial Revolution –

the First Machine Age. Of critical importance in this regard are adequate public

services, including clean water, safe food, good transport facilities, sufficient

commercial and employment opportunities, adequate housing, access to

health and educational services, and police forces to ensure public safety.

This item is an adaptation of a chapter from Valuable Digitalisation.

The challenge of digitalisation

People expect local authorities to do the best they can when it comes to such public tasks and services. In the current Second Machine Age, digital technologies play a crucial role in developing and improving these efforts. Nowadays, brick-and-mortar offices increasingly function as an auxiliary to the services offered online.

Public wellbeing has improved considerably since the Industrial Revolution – the First Machine Age. Of critical importance in this regard are adequate public services, including clean water, safe food, good transport facilities, sufficient commercial and employment opportunities, adequate housing, access to health and educational services, and police forces to ensure public safety. People expect local authorities to do the best they can when it comes to such public tasks and services. In the current Second Machine Age, digital technologies play a crucial role in developing and improving these efforts. Nowadays, brick-and-mortar offices increasingly function as an auxiliary to the services offered online.

There is a growing awareness that digitalisation is not just a means to streamline operations. It is not only changing society, it is also changing government. Digitalisation impacts on the quality of many public services and public values, from health to good and affordable transport and a warm home. The VNG’s (Association of Netherlands Municipalities) Digital Agenda for 2020 illustrates how digitalisation is generating numerous new policy practices, ranging from basic digital facilities, support for economic activity and a pleasant living environment to improvements in mobility and the use of big data in public spaces. It shows just how important data flows are to local government and the welfare of local communities.

Public innovation specialist Albert Meijer calls this a ‘datapolis’, a community of citizens who use data collectively to safeguard both individual and collective interests. How we shape digitalisation plays an important political role in this context.

This article outlines how public values can inform the process of digitalisation. Digitalisation increasingly colours how people perceive government, and, because of the rise of the Internet of Things, it also has a growing influence on the physical environment. After a brief explanation, we describe how digital technology is being used to improve local government services. We review a series of public values in that context, from privacy and autonomy to control over technology and the balance of power.

We show how local authorities can mitigate the downsides of a data-driven economy. We then look at how local government can retain control over technological systems that are crucial to the provision of public services. We do so by discussing the example of digital lighting grids (in which lampposts are fitted with data-generating sensors). We conclude by explaining how politicians and policy makers can allow public values to inform digital innovation.

Digitalisation impacts on the quality of many public services and public values, from health to good and affordable transport and a warm home.

Meta-utility

In another article we described our living environment as an array of machinery, a set of technological systems and devices that make all sorts of public services and facilities possible. The First Machine Age gave us machines that extended our physical capacities. We are now living in the Second Machine Age, the epoch of devices that extend our capacity to observe, to think, and to control our muscles.

The Internet of Things can be regarded as an extension of our nervous system. In other words, it is a type of nervous system: sensors are artificial senses, computers and AI increase our powers of cognition, and actuators make it possible to act remotely. This digital network therefore offers us the opportunity to optimise and control utilities that were first developed in the Industrial Age. The Internet of Things, in fact, a mega-utility, an IT system that impacts all other existing general amenities, tellingly illustrates the importance of digitalisation.

The data-driven economy and society

Much of the machinery of the First Machine Age required oil to operate. Data is the oil of the Second Machine Age. And like ‘Big Oil’, ‘Big Data’ must be collected and processed before it becomes useful. Some commentators refer in this connection to the ‘data value chain’, which consists of three parts:

- collecting data,

- analysing data,

- and intervening in our world on that basis.

Numerous digital technologies can be used in this process: sensors for data collection, algorithms for analysis purposes, and robots that perform physical actions. This is how digitalisation gives rise to a data-driven economy and society.

Better municipal services

According to big data expert Alex Pentland, data can help us maintain and improve public facilities. He believes that the trick is to upgrade the systems that underpin society – healthcare, education, transport, energy supply, waste processing, food supply, recreation, and so on – by taking advantage of ‘digital feedback technologies’. We can make these systems more efficient and effective by creating public data pools that respect personal privacy. Legal standards and financial incentives should encourage owners to share data, while at the same time serving the interests of both individuals and society as a whole.

In the city

The public authorities in various local communities work with other actors to collect all kinds of data that will help them to perform public tasks and attain social aims more efficiently. One well-known case concerns Stratumseind, an entertainment district in the city of Eindhoven. To improve safety and increase the area’s appeal, it has been converted into the living lab ‘Stratumseind 2.0’ over the past few years, with all sorts of sensors being installed that measure noise levels and track human behaviour. One project is investigating whether street lighting can reduce or prevent undesirable behaviour. In the town of Enschede, commuters can use an app that alerts them to alternative travel routes. The app uses a bonus system to encourage people to travel by bicycle. The app is so successful that it has been unnecessary to add more roads, saving the local authority a lot of money. And cycling may also help to improve public health.

In the countryside

The P10, a partnership of large rural districts, also wants to experiment with smart mobility, domotics (home automation) and innovative digital services in a bid to maintain the appeal of living, working and undertaking creative activity in rural areas. The island of Ameland is working on building a green energy system that will make sustainability affordable. Intelligent systems are used to even out fluctuations in supply and demand. The inhabitants of Partij, a small village in the Province of Limburg, used data from Strava, the running app, to tell the local authority about hazardous traffic situations. Improvements were made to the relevant road based on this information. The Town of Zuidhoorn in the Province of Groningen has used blockchain technology to modernise the Child Assistance Package, an allowance for children whose parents earn a minimum wage.

These activities and initiatives appear to support Pentland’s claim that the data-driven society can effectively meet all kinds of individual and collective needs. Reality is at odds with Pentland’s technological dream, however, with conflicting interests and clashes between public values and new technology.

Action and reaction and inequity and inequality

Digitalisation is by no means a friction-free process. It can generate turmoil and social unrest that require a response from politicians and policy makers. In Amsterdam, the widespread use of Airbnb, the digital marketplace for letting and booking private overnight accommodation, resulted in illegal room rentals, inconvenience and nuisance. Increasingly, local residents objected to having noisy, partying tourists in their neighbourhoods. As a result, at the end of 2016 the City of Amsterdam placed an annual sixty-day limit on Airbnb flat rentals. It put further limits on Airbnb rentals in early 2018 by cutting the maximum rental period to thirty days.[1]

Questions have also been raised about Uber, specifically about its drivers’ earnings and working conditions, and about compliance and monitoring.[2] Digital platforms make use of infrastructures that are maintained by public funds, and so do many components of the sharing economy. Initially, sharing flats or cars was regarded as a socially beneficial form of sustainability that was also beneficial for people’s wallets.

By now, the huge success of Airbnb, Uber and other platforms illustrates that the sharing economy can also lead to rental or employment practices that break the law, evade social insurance contributions and cause unwelcome disruption. These adverse effects end up on the desks of local politicians and policy makers, who are expected to put a stop to the abuses. Are these practices illegal or unfair and, if so, how can they be combated? Politicians and policy makersin Amsterdam and other European cities have slammed on the brakes and introduced rules designed to better manage digital innovations in this domain.

In Amsterdam, the widespread use of Airbnb resulted in illegal room rentals, inconvenience and nuisance.

Algorithms under fire

Big data companies regard algorithms as the foundation stones of their business, but they may conflict with the public interests and tasks for which government is responsible. A computational model that streamlines processes for one person may be disadvantageous for another because it curtails his or her autonomy or erodes human dignity. In Weapons of Math Destruction, Cathy O’Neil (2016) gives examples of how the use of big data promotes discrimination and social inequality. She contends that ‘Models are opinions embedded in mathematics’ (2016, p. 21). Predictive models can be powered by incorrect assumptions, or prejudices, leading to adverse consequences. A simple example suffices to prove our point: if employers refuse to hire someone with a criminal past because a model predicts a pattern of recidivism, that person is more likely to commit a crime, confirming and reinforcing the pattern. These are the sort of loops in the data value chain (i.e. collecting and analysing data and taking action based on that information) that can have a major impact on people’s lives.

As a result, O’Neil (2016) asserts that algorithms are a danger to society if they are

- not transparent,

- applied on a massive scale,

- and have harmful social consequences.

Using algorithms in a socially responsible manner would thus involve:

- making them transparent,

- using them on a limited scale at first so that any harmful effects can be eliminated,

- and continuing to track their social impact when applying them on a larger scale.

These principles underpin the Algorithmic Responsibility Bill passed by New York City Council in December 2017. The bill established a task force that monitors the fairness and soundness of algorithms used by city agencies.

Infrastructures: definitive decisions

One-way or circular

Technological choices can have very far-reaching consequences for society that are difficult to reverse. A case in point is the design of our sewage system during the First Machine Age. In the nineteenth century, London opted to build a new underground pipe system that would transport the surfeit of faecal matter resulting from urbanisation to the sea. Human faeces had previously been collected and used as agricultural manure. The controversy about the new pipe system was settled when a heat wave hit the city in the summer of 1858, causing an immense stench known as the ‘Great Stink’.

Instead of a closed-loop system, politicians and policy makers opted for a one-way sewer system. Their decision led to a gigantic sewer network that rid Londoners of the stench by sending their dung into the sea. We no longer consider this an efficient solution: our toilets use clean water to flush away useful raw materials. Yesterday’s technological solution is today’s challenge: how do we move from one-way to more sustainable, circular communities?

In the same way that an historical preference for non-circular sewage systems still defines our approach to excrement, the choices made by today’s politicians and policy makers in constructing smart infrastructures and utilities will continue to define the nature and quality of our streets and squares for a very long time to come. In this section we discuss the emergence of smart lighting grids, a billion-dollar market worldwide. Another term for smart lighting is ‘connected lighting’, which makes clear that public lampposts are connected to the internet. Smart lighting grids are therefore an example of Internet of Things (IoT). The City of Eindhoven is experimenting with smart lighting in five ‘living labs’. The municipal lighting innovation programme will run until 2030. Eindhoven is involving industry, research institutions and the public in the innovation process and wants digitalisation to serve public interests. The question is: how?

More than light

Public lighting has traditionally been the responsibility of local authorities, but intelligent lampposts enable commercial opportunities that have not escaped the notice of industry. Smart lighting grids create a basic infrastructure that supports many other innovations. Sensors can be fitted that will generate money-making data streams. High-mast lighting can be used to project advertisements or as a charging station for electric scooters or cars. Lampposts could also feature in the roll-out of the fifth generation (5G) mobile network, which will require numerous new GSM towers. The 5G network will make all sorts of IoT applications possible, including the robot car. Electricity, sensors and the internet converge in smart street lighting and that is why companies such as Philips, Vodafone, KPN, Siemens, Cisco, IBM and the Bouwfonds (a Rabobank investment company) are interested in this innovation. The modernisation of the municipal lighting grid thus involves economic and societal interests that far exceed the purpose of lighting itself.

The City of Eindhoven saw this development coming to some extent. With a visionary roadmap as inspiration, it invited tenders for municipal lighting in 2014.[3] The aim was to continue to promote Eindhoven as the ‘City of Light’ and, by 2030, to develop an integrated ‘Smart Lighting Grid’ to support existing and new services that will improve the quality of life in the city. Philips Lighting and Heijmans Roads submitted the winning tender. Under the contract that the local authority concluded with the Philips/Heijmans consortium for a 15-year period, there is leeway for new parties that want to use the lighting grid for their own products or services.

Technological control

One important issue is who controls and exercises authority over the digital lighting grid, including lampposts, sensors, software and data. Who owns what and under which conditions, and who is responsible and liable? Eindhoven retains ownership of the high-mast lighting systems and the land beneath them. Philips/Heijmans manage the smart lighting grid. The data transmitted by smart luminaires is stored on a Philips server.

However, the city can access the data at any time and is also authorised to take control of the grid when public interests are at risk. In addition, it has commissioned software and equipment for the grid that keep data transfer as open as possible. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen how the city will in fact maintain control and continue to exercise authority over the smart grid. The open innovation platform that Eindhoven is developing must be viewed against the backdrop of a shifting global market. Eindhoven may be the birthplace of Philips, but like other large enterprises the company aspires to global market leadership. The political context also plays a role in the development of public amenities.

Several decades of austerity have reduced the municipal budget of Eindhoven and other communities year on year. In addition, local governments are unwilling to lag behind economically and want to continue attracting young and creative talent. All this has led to a situation in which they are tempted by enterprises clamouring to manage crucial amenities in a bid to improve their position in the data economy. The opposite side of the coin, in the worst case, are poor, isolated, technology-unaware communities. It will be clear that this in fact implies the privatisation of the electricity grid and all associated data on public spaces

Coordination by national government

In short, if local authorities want to retain control and exercise authority over new smart electricity grids, they will have to stand together. Since the national public interest is at stake, the national government also has an important role to play in this context. If it fails to do so, it is possible that a few high-tech giants, such as Philips and Google, will eventually also control many of these digital networks. Once they do, the focus will not be on public interests and public values but on economic interests.

Action informed by public values

This chapter shows that it is prudent to consider the merits of digital innovations on a case-by-case basis. What is the expected impact on society? Which public values are at stake? Digital technologies that can deliver a selfsupporting, sustainable energy grid should thus be viewed in a different manner than an automated decision system that has implications for our personal autonomy. Public values must inform such decisions so that we can consider digital innovations in a broader social context and develop them in a socially responsible manner. The key is to strike a sound balance between private and public interests in the Second Machine Age, where data is the new oil and the digital network a meta-utility. This is all the more important given the context of the emerging Internet of Things: digitalisation will increasingly define the nature of the physical environment in public spaces and the extent to which commercial interests prevail there.

Various challenges

The Information Society and Government Study Group believes that government faces several different challenges. It must do more to organise matters in response to the public’s expectations and needs. And it must identify clearly-defined frameworks and long-term objectives for digital society. Government legitimacy depends on the level of citizen’s trust in public authorities, how these authorities manage and use information. Another major challenge is the scalability of successful products. Digital technologies are often impeded by the fragmented nature of public administration. The Study Group’s final observation is the critical lack of digital knowledge and skills within government. That knowledge is regarded as a core competence for the performance of government’s public tasks.

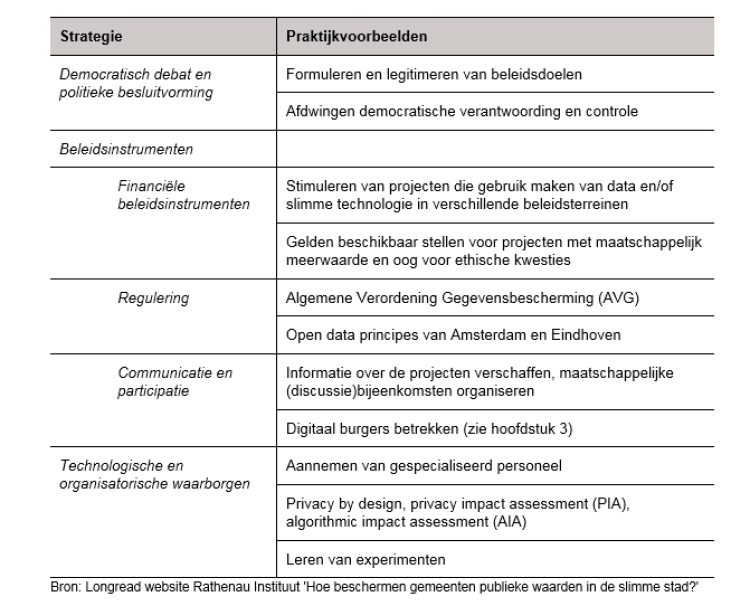

In the light of our findings and the challenges described above, we outline an mode of action for politicians and policy makers that will allow them to address these challenges responsibly and effectively (see Table 2). Our proposal is based on a system of multi-level governance in which local, national and international policies (e.g. the General Data Protection Regulation) are mutually complementary and mutually reinforcing where possible. It is based on three foundations:

- democratic debate and political decision-making

- policy instruments

- technological and organisational safeguards

Democratisch debat en politieke besluitvorming

De gemeentelijke visies die aan de projecten op het gebied van data en slimme technologie ten grondslag liggen, zijn in principe gevormd via democratisch debat en politieke besluitvorming. Via democratische weg bepalen en verantwoorden de betrokken wethouders de doelstellingen die

Democratic debate and political decision-making

The municipal strategies that underpin data and smart technology projects have, theoretically, taken shape through a process of democratic debate and political decision-making. The executive councillors involved use democratic means to identify and account for the objectives that legitimise innovative projects. They also define and account for the strategies required to deal with the associated social and ethical issues. Such debate and the system of checks and balances in municipal decision-making are, in principle, meant to safeguard public interests. It is also at this level that overall reflection is needed on the relationship between the different domains of digitalisation. Innovations that have a bearing on mobility, sustainability or the design of public spaces are intertwined.

Their cumulative impact and wider influence require a broader discussion. Policy instruments Strategies meant to safeguard public interests involve creating the right conditions to apply data and smart technology in municipal projects. Local authorities can, for example, create these conditions by issuing regulations, through their financial policy, and by communicating with or fostering the participation of city dwellers. Municipal governments can draft their own bylaws, policy rules and guidelines. They can also use their funding policy and purchasing terms and conditions to influence the accessibility of data generated partly with public funds, for example in the case of smart lighting grids –the open data principles adopted by Amsterdam and Eindhoven can serve as a guideline. They can further explain the projects, the goals and the means (technology, data, algorithms) to local residents.

In doing so, they must be careful not to use veiled language, and they must be open about the various interests at stake and welcome discussion of the possible impact of a particular innovation. Even better is to actively involve local residents in projects, for example by organising participatory design sessions or by setting up panels to identify specific needs and wishes with regard to new technologies.

What implications does smart technology have for how we co-exist physically, culturally and socially?

Technological and organisational safeguards

To safeguard public values, local authorities can also use organisational and technological instruments. A number of such instruments have been made mandatory by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). According to the GDPR, the public authorities of larger communities are expected to hire specific staff, such as data protection officers, to monitor data system security and the protection of privacy. Focusing on privacy by design and providing practical tools to innovators (see the next case history, ‘Rules for sensors in public spaces’) makes it possible to safeguard the public values on which these legal frameworks are based.

The ‘privacy by design’ principle involves designing IT systems in a privacy-friendly way. Our final recommendation concerns workflow management software. This software helps to document all the options and limitations of data collection, analysis and use, thereby improving transparency and accounting for how the municipal government deals with data. ‘Learning by doing’ is an organisational strategy. Many digitalisation projects are designed as experiments. Interim monitoring and evaluation of such experiments make it possible to assess the extent to which autonomy, trust, responsibility and other data-related issues are properly covered. A privacy impact assessment (PIA), as defined in the GDPR, can be an instructive tool in that context.

What do we want? The bigger picture

Local authorities can use these three strategies to guide innovation and ‘bring technology home’. They must, however, always consider the bigger picture of society and that means examining the advisability of data-driven and smart technological systems in Dutch communities: what implications does smart technology have for how we co-exist physically, culturally and socially? In an international context, the question is to what extent Europe will follow its own digitalisation pathway, based on important values such as inclusiveness and sustainability. In the end, the political question goes far beyond mere decisions about technology and the necessary safeguards.

Read more

- Innovating for societal aims

- How are municipal governments protecting public values in the smart city?

- Using Sensor Data for Safety and Quality of Life

Sources:

[1] Volkskrant 11 januari 2018, Amsterdam legt Airbnb verder aan banden.

[2] Volkskrant 12 januari 2018, Uber legde eigen computers lam tijdens invallen inspectie

[3] Selectieleidraad Implementatie Visie en Roadmap stedelijke verlichting, Eindhoven 2030, gemeente Eindhoven, april 2014.