How are municipal governments protecting public values in the smart city?

Smart cities have wonderful aims, such as innovation and public participation. But digitising cities can put such values as privacy, security, justice and autonomy under pressure. In the third article in our series on the smart city, we ask what municipal governments are doing to protect their residents in the digital era.

This article is one in a series of three.

We conducted interviews, attended meetings and inspected policy documents to search out the specific strategies deployed by the Netherlands’ five largest cities, i.e. Eindhoven, The Hague, Utrecht, Rotterdam and Amsterdam (the ‘G5’ cities). We found that their municipal governments are protecting public values in the smart city in three ways:

- through democratic debate and political decision-making

- with policy instruments

- with technological and organisational instruments.

Below we describe real-life examples of each strategy in the five cities.

Not a job for cities alone

The municipal government is not the only party responsible for protecting privacy, safety and security, autonomy or justice. These issues are above all a question of multi-level governance. There are several tiers of government involved, from local to international, as well as private parties such as businesses, civil society organisations, researchers and city-dwellers themselves. In our study, we concentrated on the instruments available to municipal authorities. We did this by analysing municipal policy documents and conducting interviews with municipal professionals who are responsible for smart city projects.

1. Democratic debate and political decision-making

Municipal governments draw up short-term and long-term plans for their city through democratic decision-making processes. That means that policymakers consult the municipal council about their plans and, in many cases, also talk directly to local residents and other stakeholders. It is during such consultations that the relevant policymakers explain their plans: the executive councillors account for their decisions, monitored by the municipal council.

Smart city projects are a means to achieve long-term plans. The relevant executive councillors are responsible for setting the project objectives and for implementing strategies that address the societal and ethical issues involved. Municipal councillors sometimes have critical questions about smart city projects. For example, Fatima Faïd, who represents a local political party (Haagse Stadspartij) in the municipal council of The Hague, questioned a fraud detection project there. She doubted the fairness of making the variable ‘holidaying in the same country’ a risk factor in the analysis. In her view, this could well generate more false positives for people from a migrant background, as they customarily visit relatives in their country of origin. It was also not clear to the municipal councillors what other variables were included in the analysis, who had selected them and on what basis. Faïd further questioned whether the data-driven measures were proportionate to the fraud that they were meant to detect. In their response, the municipal executive argued that ‘the variables were selected by official means based on cases of fraud that had been successfully proven’, and that the data analyses would improve the efficiency of fraud detection. But this particular debate appears to be an exception; in other cases, municipal councils tend to focus mainly on multi-year plans in their debates, with specific projects often escaping their attention. Smart city projects are usually left to the municipal professionals.

The general public also knows little about such projects. Municipal governments do make attempts to launch a broader debate. All five of the cities have entered into partnerships – albeit modest ones – with civil society organisations and individual researchers to actively encourage public debate about the smart city.

2. Policy instruments

To protect public values in smart city projects, municipal governments can use policy instruments to establish appropriate underlying criteria for data collection, analysis and use and for the deployment of smart technology. They can do this by enacting legislation, in their financial policy, and by communicating with the public and encouraging public participation.

Legislation

Municipal governments can draft their own bylaws, policy rules and guidelines. Smart city projects are also subject to national or EU legislation. The professionals we interviewed cited the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as especially relevant for their projects. The GDPR creates a statutory framework and specific instruments for data protection. Although it will only become effective on 25 May 2018, it is apparently already the most important legislative framework. For example, it has already inspired smart city professionals to adopt a number of technical and organisational measures (see also item 3).

In addition to existing legislation, some municipal governments are adopting extra rules for the use of data or smart technology.

- In September 2015, the municipal executive of Eindhoven adopted eight policy principles governing disclosure and accessibility of data collected, tracked or generated in public spaces. Based on these principles, the municipal government refused to pay TomTom for data collected in public spaces and advises others to follow its example. Eindhoven’s executive councillor Staf Depla asserts that everyone should be able to earn money from products and services based on data collected by sensors in public spaces, as long as the privacy of private citizens is respected.

- In February 2017, the municipal executives of Eindhoven and Amsterdam issued a joint policy memorandum stating their ‘open data principles’ [1]. Their aim is to ensure the accessibility, interoperability and transparency of data, as well as the privacy of people in their cities. These principles are also meant to even up the balance of power between public and private parties in smart city projects. Specifically, one of the principles, i.e. ‘data is regarded as open and shared unless…’, entrusts ownership of data to the public.

Financial instruments

The five cities reserve budgets to encourage experimental smart city projects, the aim being to provide more efficient and effective services and encourage innovation or public participation. They also acquire funding through EU and other research projects. By entering into partnerships or issuing tenders, they work with businesses and knowledge institutions on smart city projects. They can set conditions for project funding. For example, the cities of Eindhoven and Amsterdam expect project partners to comply with their open data principles. For the City of Eindhoven, that means that the municipal government has free access to the data that Philips collects with its new smart street lighting.

Communication and public participation

By adopting communication policy measures, our smart city professionals aim to inform city-dwellers about the implications of municipal projects. For example, they find it important to inform the public about projects for transparency and control purposes. The information they provide concerns the technology, data and algorithms being used in the projects, as well as the underling project objectives. A number of our interviewees said that their organisation had only just started communicating with the public about these matters. The civil society organisations confirm this and are critical of project transparency and verifiability. In their view, municipal governments often use veiled language. Why would the municipal authorities refer to ‘explosion sensors’ and not to digital microphones that record fireworks and other noise? (interview with SETUP, Utrecht). This makes it difficult for the public to grasp how such devices operate and what their impact might be.

Another municipal strategy for actively involving a target group in a smart city project is ‘participative design’. Future users contribute to the design in such instances, often in cooperation with civil society organisations. One example is a project in the City of The Hague meant to help senior citizens live independently for longer using digital technologies. A panel of senior citizens was involved in the design process. They tested the technology and discussed their specific needs and concerns with the project team. The team ultimately designed the system based on these discussions.

Civil society organisations also take steps to communicate with the public and encourage its participation. For example, they hold meetings, sometimes sponsored – at least in part – by the municipal government. Or they organise eye-catching activities to raise public awareness of smart technology and data in the city. Two examples:

- A data walk in Rotterdam. Participants are asked to identify data collection or utilisation points in public spaces. The participants then discuss the purpose of the data points and who is behind them.

- An artist developed a ‘discriminating coffee dispenser’ for SETUP in Utrecht. The dispenser serves good- or bad-tasting coffee depending on the user’s postal code. It illustrates how data analysis can lead to profiling (and possible discrimination), thereby raising this issue for discussion.

3. Organisational and technological safeguards

In their efforts to protect public interests, municipal governments can also alter their organisation or the technology. They can hire specialists, redesign processes or customise technology.

Organisation

Municipal governments can make organisational changes by hiring specialists for specific tasks. In our interviews, they mentioned the following:

- Data protection officers. They monitor data system security and data protection. This measure anticipates the rules laid down in the EU’s GDPR, which states that data protection officers must be able to act independently.

- Data scientists, responsible for the quality of databases and data analyses.

- Cybersecurity officers. The City of Rotterdam recently hired several people in this position.

- Qualitative researchers. The City of Eindhoven appointed a qualitative researcher to talk to local residents in specific neighbourhoods. It will combine this qualitative data with quantitative data to gain a more complete picture of the situation.

Municipal government are also redesigning processes. Various G5 cities are attempting to mitigate the limitations of datafication by applying other forms of evidence alongside quantitative data. The City of Utrecht, for example, has organised expert groups in which professionals interpret data analyses based on their own real-world expertise.

In their projects, all the municipal governments operate on the principle of ‘learning by doing’. The vast majority of projects that we reviewed in our study were designed as experiments. They are small in scale and meant to test new data analysis techniques or technologies. The municipal governments conduct SWOT analyses beforehand and monitor and evaluate progress throughout the course of the project. They make use of a range of different instruments for this purpose, such as the social cost-benefit analysis applied in the City of The Hague. Another instrument is the Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA), used to assess the privacy risks involved in data collection, analysis and use in advance and to design measures to reduce such risks. The EU’s GDPR will make DPIA compulsory. Finally, the City of Utrecht uses an Ethical Data Assistant, an instrument that supports a broad assessment of a project’s societal and ethical impact. The Ethical Data Assistant considers not only privacy issues but also autonomy, trust and responsibility.

Technology

Another way to draw attention to public values is to alter the technology. Two examples:

- Privacy by design. The aim is to design IT systems to be ‘privacy-friendly’. Municipal governments also adhere to the principle of data minimisation: the technology only collects data that is absolutely necessary to achieve specific objectives. The City of Utrecht issued a privacy bylaw to that effect and applied it to the bicycle parking facility project described earlier. The cameras monitoring the facility only count the empty parking spaces for immediate computation, the results of which are conveyed to digital signboards and a specified app. They do not record the images (interview with SETUP).

- Workflow management software. This software helps to document all the options and limitations of data collection, analysis and use, thereby improving transparency and accounting for how the municipal government deals with data.

Everything covered?

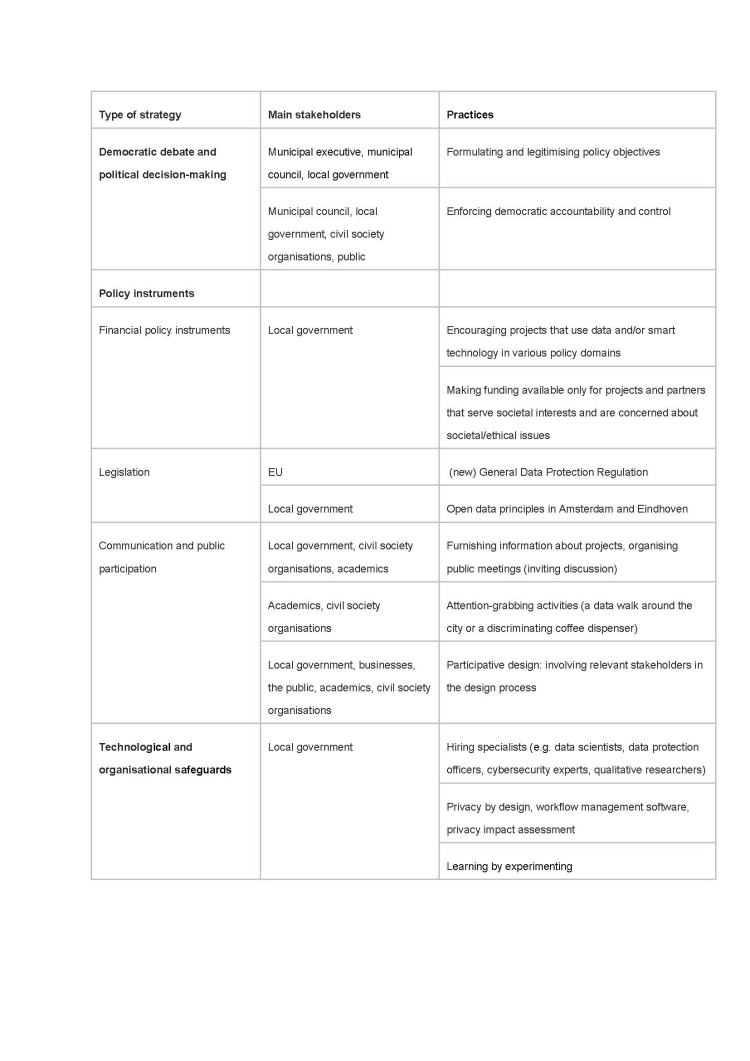

Our study produced the following list of strategies deployed by the five largest Dutch cities:

How effective are these safeguards and measures in real life? Are the strategies discussed above sufficient? Or do gaps remain in smart city governance?

To find out, we have commenced a study in the City of Eindhoven. The municipal government says that its smart city projects are pushing legal, administrative and ethical boundaries. Our study will investigate a number of these projects in-depth. By doing so, we hope to continue to encourage public debate about the smart city, and more specifically about the desirability of data-driven and smart technological systems in Dutch cities.

[1] In a follow-up study, we will explore the extent to which these open data principles can be traced back to existing legislation and the degree to which they are unique.