Innovating for societal aims

In this chapter, we draw attention to a new generation of transformative innovation policy, one that aims to support transition

paths and solutions addressing the major societal challenges of our time. As local organisers who often see and feel such problems most directly, municipal authorities can play an important role in this context by supporting promising innovations.

But they cannot do this on their own.They need to cooperate with local companies, knowledge institutions, professionals, users, citizen initiatives, residents and/or civil society organisations. If they mean to scale up local solutions, they also need to cooperate with other municipal authorities, with regional and national authorities, and sometimes with other European governments as well.

This article is an adaptation of a chapter from the report Valuable digitalisation.

Innovation policy for societal challenges

The grand challenges facing society – climate change, sustainable transport and mobility, renewable energy, food security and an ageing population – have become the predominant force driving knowledge and innovation policy in recent years.

The European Union was a forerunner in this respect with its Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation. A significant share of that programme budget is reserved for research that seeks to find solutions for seven ‘societal challenges’. Those challenges have now also permeated national and regional knowledge and innovation policies.

The focus of the Northern Netherlands’ smart specialisation strategy, for example, has shifted to four of these societal challenges instead of its sector-driven policy. In the Netherlands’ national innovation policy, the top economic sectors have indicated, at the Government’s request, how their agendas and activities are addressing societal challenges. The Government coalition agreement refers to a reorientation in the top sectors policy towards societal challenges. The aim of innovation policy has always been to help companies or business sectors become more innovative and to ensure robust innovation ecosystems. In its new innovation policy, the Dutch government uses targeted measures to encourage innovative solutions to complex and persistent societal problems.

The underlying premise of the new innovation policy is that government should actively help to find new ways to tackle the challenges of the twentyfirst century, according to Mazzucato and Raworth. The wish to put innovation policy more firmly at the service of societal challenges has now gained broad support.

INNOVATION POLICY

We can summarise the evolution of innovation policy as follows. Until the 1980s, government focused heavily on stimulating R&D investment by offering subsidies and tax breaks and by protecting intellectual property.[1] ‘Market failure’ gave government policy legitimacy: companies are less inclined to invest in R&D than society would like because their competitors will also benefit from the results. From the 1990s onwards, it became popular to think in terms of innovation systems, with government’s main role being to repair ‘system failures’.

During this period, innovation policy was firmly geared towards connecting the actors in the innovation system and encouraging publicprivate partnerships (PPPs).[2] Recently, we have seen the dawning of a third generation of ‘transformative’ innovation policy, the aim of which is to promote innovations that are beneficial to society. Government is now more closely involved in the content of innovation, in that it helps to find innovative solutions and transition paths addressing pressing societal challenges, such as the transition to a low-carbon or circular economy. In short, innovation policy has gained legitimacy not only from market and system failure, but now also from transition failure.

The importance of co-creation

Transformative innovation policy calls for new ways of thinking and working, both in policymaking itself and in the way research and innovation are managed and organised. One factor is that technological innovations alone will never be enough. Social innovation in existing corporate, professional and user practices is often much more important. Hence the need to involve behavioural scientists, companies, users, public initiatives, interest groups and others in the search for new solutions. Innovation policy addressing societal challenges must be implemented using new policy tools based on the ‘co-creation’ of innovation.

In this case, cocreation means that end users, professionals, members of the public and/or civil society parties play an active role alongside researchers and technology developers in setting the agenda for and developing innovative solutions that actually work in the real world. In societal transition processes, practical or experiential knowledge is often just as important as scientific and technological knowledge and skills. Government is there to facilitate, coordinate, incentivise and/or orchestrate collaboration.

Another aspect of transformative innovation policy is that in the long run, major societal challenges must be turned into tangible missions and programmes in which existing and potential solutions can be explored and tested. An experimental approach is necessary because transition paths cannot be designed in advance. The challenge is to organise a joint quest to identify advisable and feasible transition paths.

Beckoning local scale

Local and regional authorities play an important role in this new innovation policy. That is first and foremost because societal problems are felt most acutely in cities and villages and because local authorities have a responsibility to address them. Their responsibility has grown heavier in recent years as the national government has undertaken various decentralisation operations.

Second, that is because the grand societal challenges can be broken down into ‘bite-sized’ elements at local level. There, it is possible to undertake experiments to identify promising solutions and transition paths. For example, experimenting locally with new solutions obviates the need to immediately change national policy frameworks and existing structures. Moreover, cocreation is most effective when organised around a local initiative or experiment; it is often easier to build mutual trust and share personal knowledge at the local level.

City Deals: multi-level cooperation

But local government cannot do it on their own. To ensure that local initiatives contribute to societal transitions on a larger scale, it has to cooperate with other municipal, provincial and national authorities, water boards and sometimes even the European Commission. The aim of a challenge-driven innovation policy is to arrive at a ‘multilevel’ division of labour in which each tier of government contributes to finding solutions and transition paths addressing societal challenges by virtue of its own competencies and responsibilities.

One example would be the ‘City Deals’ that the national government is concluding with local authorities. Below, we first address the role of local government in tackling societal challenges. We then explain the ‘living lab’ phenomenon as a promising tool for transformative innovation policy. In theory, living labs offer a real-life environment in which multiple parties can join forces to experiment and work on innovations that address societal challenges; this makes them an interesting tool for local transformative innovation policy. In reality, however, the living lab label covers a wide variety of different initiatives, each with its own features. We attempt to create some order out of this chaos with our typology of living labs. Then, we explain how local authorities can ensure that living labs make an effective contribution to finding innovative solutions and practical transition paths for the grand challenges. Finally, this article concludes by listing six lessons for the new generation of transformative innovation policy.

The need to do something to address the issues of climate change, environmental pollution, public health, poverty, accessibility and other mattersis particularly pressing in urban areas.

Role of the local authority

The municipal authority is an important tier of government when it comes to tackling societal challenges. The need to do something to address the issues of climate change, environmental pollution, public health, poverty, accessibility and other mattersis particularly pressing in urban areas. In addition, with their local networks of businesses, knowledge institutions and public initiatives, municipalities offer an appropriate arena in which to work on solutions. Local networks and initiatives bring local parties together and allow them to join forces.

Copenhagen sets an example

Global challenges, for example carbon reduction, seem too overwhelming to break down into bite-sized components at local level. Even so, there is no question that local governments can work to address these types of societal challenges. Copenhagen has shown us how. As far back as 2005, the municipal government set itself the aim of making the city carbon-neutral by 2025. That gave it and local businesses and civil society organisations twenty years to take action. The grand societal challenges must be worded in terms of local missions and policy objectives that can count on public support. The next move is to develop a portfolio of initiatives that can help meet the objectives that have been set.

Societal challenges are so complex that it will take a series of (successive) initiatives to find innovative solutions that truly do support the desired societal changes. This calls on government to show leadership and develop the right expertise as the guardian of the public interest. It must show leadership by charting a course, monitoring progress and making changes where necessary, even when disputes arise and there is resistance from society. And it must develop the right expertise so that it can join stakeholders in civil society in determining which initiatives do and do not contribute to attaining the objectives of the mission. For each initiative or project, the local authorities must find a balance between managing, encouraging, facilitating and letting go.

Arnhem and Amsterdam as driving forces

A local authority can take action itself in domains for which it is responsible. Copenhagen invested in hybrid buses that reduced carbon emissions by 75 percent. But government can also force others to adopt climate-neutral practices, as recently happened in Arnhem when the municipal authority established the strictest environmental zone in the Netherlands. A local authority can also encourage and facilitate bottom-up initiatives.

One example is Amsterdam’s policy supporting residents in Amsterdam-North who want to turn their district into a circular economy; the local authority is dealing flexibly with regulations and drawing lessons from this sustainability initiative that will be useful in other parts of the city. The complexity of societal problems makes experimentation and living labs worthwhile. Such initiatives can be launched by local government itself, or undertaken by other parties, with local government simply extending the necessary permissions or going a step further by offering encouragement or outright support.

Living labs as an innovation tool

The above quote identifies two essential features of living labs: the real-life experimental environment (the laboratory space) and the collaborative approach to experimentation (co-creation). In practice, a host of different initiatives are given the ‘living lab’ label.

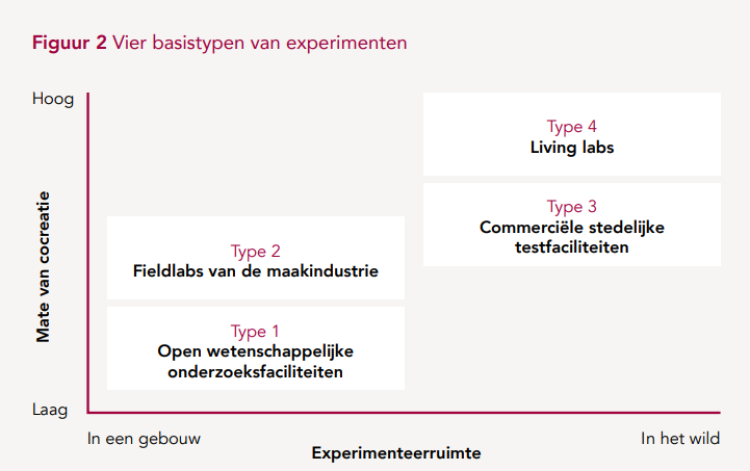

We also see initiatives that promote themselves as field labs, smart labs or something similar, without it always being clear what these terms mean. To get a better idea of what these various ‘lab’ initiatives are, we have developed a typology based on the features identified above. Figure 1 provides an overview. We explain the dimensions below.

Inside or outside the lab and level of co-creation

The first dimension is the type of space in which the experiments are organised. On the one hand, we see experiments being undertaken in clearly defined laboratories, in a building or part of a building that isscreened off from the outside world. That makes it easy to control the test environment. On the other hand, there are experiments organised outside the laboratory, in a street, neighbourhood or on the outskirts of a town.

Many of these make use of digital technologies, such as digital sensors that monitor the test environment. The second dimension is the level of co-creation. If cooperation is limited to researchers and enterprises, then the level of co-creation is low. If professionals, policymakers, the public and/or civil society parties also play an active role in setting up and conducting the experiment, then the level of cocreation is high.

Type 1: Open scientific research facilities

The first type is a partnership between a knowledge institution and industry in which the knowledge institution opens the doors of its facilities to industry. These experiments generally take place in a traditional laboratory setting and the level of co-creation is limited. They tend to involve research and technology and are used by universities for knowledge valorisation purposes.

One example is the Dutch Optics Center, in which Delft University of Technology cooperates with the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) on matching new optical inventions with the needs of businesses in order to drive innovation and valorisation. This type aligns with first- and second-generation innovation policy, which emphasises valorisation and innovation in industry but without government providing any explicit guidance. The aim is to use technology to deliver new products and services that will generate employment and revenue in industry.

Type 2: Field labs for the manufacturing industry

In the second type, a group of enterprises works with knowledge institutions to digitise and automate industrial processes. These initiatives often have support from a regional or local authority that is looking to innovate regional manufacturing and boost its competitiveness. The experiments are usually conducted in a physical building with a simulated industrial setting.

The level of co-creation is limited because no end-users, members of the public or civil society parties are (or need to be) involved. The Dutch national government’s Smart Industry policy has given rise to many different field labs.

For example, the Sustainability Factory in Dordrecht shows employees and students how to work with new digital tools in the maritime and energy sector. This type also aligns with first- and second-generation innovation policy. Its purpose is to boost competitiveness in manufacturing and, as a result, maintain and improve direct and indirect employment in the relevant industry.17 It is not meant to help discover innovative solutions and practical transition paths for societal challenges.

Type 3: Commercial municipal test facilities

Both the space involved and the scope of collaboration are broader in commercial municipal test facilities. In these initiatives, an enterprise works with knowledge institutions and local politicians and policy makers to test new products or services in a real-world setting (often in the open space of a street or neighbourhood) with end-users. One good example is Flo, an ‘intelligent’ traffic light that is meant to get bicycle traffic flowing more smoothly and is now being tested in Utrecht and Eindhoven. Another is InnoFest, which uses music festivals in the northern part of the Netherlands as a test environment for all sorts of innovations, from temporary insurance to new types of sewage systems.[4]

Because this type of test facility usually takes place in public places, local authorities are involved in issuing permits and in monitoring public spaces. The local authority can also join the initiative as a partner if the innovation contributes to solving municipal problems or improves public services. This type of facility can help embed new technologies in the municipal organisation and in public spaces. One well-known risk, however, is that private corporate interests (especially those of large enterprises) may prevail over the public interest if the authorities fail to offer enough counterweight (in terms of actual content).

Type 4: Living labs

The fourth and final type is the living lab. Living labs feature broad and ‘inclusive’ collaboration between knowledge institutions, enterprises, professionals, civil society organisations and the public. The experiment furthermore takes place in a real-world setting (neighbourhood, urban district or city-wide). The participants in living labs seek solutions to complex societal problems. One example is the transition to a circular economy being undertaken in the Buiksloterham district of Amsterdam. One of the projects involves applying certain recycling principles to local waste water treatment by the local water management provider. After testing, the same principles can then be applied in other places around Amsterdam.

Such experiments can help local authorities define the overall shape of societal transitions at local level. They explicitly guide innovation policy in this type of experiment, and play multiple roles: they are responsible for public spaces, they serve as co-owners of the problem, they provide a portion of the funding, they generate knowledge, and so on. Whereas business interests dominate in the first two types, in this case the focus is on the societal issue and innovation is a necessary part of the transition.

Living labs: a tool for addressing societal challenges

The living lab (type 4) is a promising tool that can be used to address societal challenges in local communities and regions. Starting with a specific, local problem makes it possible to devise and test new approaches and solutions.

Not all living labs are scalable

To truly make a contribution to large-scale societal transitions, the knowledge and experience gained in local experiments cannot remain stuck at the local level. It is not easy to scale up promising results, however. Solutions that appear to work in the specific context of a local lab are often the result of customisation, adapted to local conditions, and it is not at all certain that these solutions will work well elsewhere.

What works in a living lab in one town need not necessarily work across the entire town, or in another town or city. Neither does it go without saying that local participants want to invest time in transferring and sharing knowledge. Their implicit knowledge and experience must be made explicit so that it leads to insights that are also useful elsewhere. It is quite an effort to transform the knowledge and experience gained by participants in a local lab into practical knowledge that other communities can use.

For living labs to be effective at addressing societal challenges, they must form part of an integrated approach in which local authorities learn from one another, and in which the national government acts as facilitator and coordinator. Where appropriate, cooperation could also be established at European level to learn from experiments in other countries. Mutual learning means that local authorities do not have to reinvent the wheel; ideally, living labs should be part of a coordinated approach that makes clever use of their differences to produce robust, scalable solutions.

Om daadwerkelijk te kunnen bijdragen aan grootschalige maatschappelijke transities, moet de kennis en ervaring die met de lokale experimenten is opgedaan niet blijven steken op lokaal niveau.

Case study: Medical Delta Living Labs

Several localities are currently experimenting with innovation coordination methods. One interesting case concerns the Medical Delta Living Labs in the Province of Zuid-Holland.

The ‘Medical Delta’ – a network of life sciences, health and technology organisations based in the Rhine Delta region of the Netherlands – is attempting to coordinate a network of living labs in various care institutions (university hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation centres and the home nursing environment). They share their knowledge and experience through the Medical Delta Living Lab Academy, providing useful information on what does and does not work in certain situations and why this is so.

The Medical Delta also participates in the Smart Industry Field Labs programme and in the Health Living Labs run by the European Institute of Technology (EIT). The Field Labs programme coordinates fifteen field labs in the province with a view to connecting and encouraging mutual learning.[5] EIT shares knowledge and experience at the European level. The Medical Delta can therefore benefit from an extensive network.

Bureaucracy versus enthusiasm

One of the pitfalls of coordination is that it can lead to bureaucratisation and kill off the very enthusiasm and creative entrepreneurship at local level that helps living labs to thrive. The challenge is to combine local energy with supralocal learning. Local residents’ and administrators’ aims, expectations and interests are geared to their own community. Knowledge institutions and industry can help drive broader applications in response to research or commercial interests.

Local residents and administrators benefit from knowledge-sharing because it givesthem accessto useful expertise elsewhere. Parties prepared to learn from and about one another can connect through local platforms or forums that facilitate cooperation between local experiments. Regional and national authorities can play a role in increasing the impact of transition-minded initiatives (addressing societal challenges), but overarching organisations such as the VNG can also do their part to boost these initiatives

Long-term, shared strategic agenda

In many cases, the innovative solutions generated by living labs are only one step along the way to maturity. In this sense, living labs are not one-off experiments, but a series of interrelated experiments that span several years.

Testing solutions in different locations can make knowledge more robust and, eventually, allow society to learn how to organise transitions. This type of approach requires:

- a multi-year, multi-party effort;

- coordination;

- a structure that supports experimentation in several locations and over a longer period of time.

Six lessons for the future

We conclude with six lessons for the new generation of local innovation policy in which living labs can play a major role.

1 Innovation policy across multiple generations

Innovation policy has evolved acrossthree generations. In the first generation, government encouraged research and innovation in industry through direct funding and tax breaks. In the second generation, the focus was on connecting industry and knowledge institutions by encouraging cooperation in innovation systems.

The purpose of the latest generation is to provide targeted support for innovations that contribute to solutions and transition paths addressing societal challenges. Innovation is not an end in itself, but a means to attain certain societal aims and to spur certain societal transitions. The three generations co-exist, but each one comes with its own policy aims and tools.

2 Each generation of innovation policy has its own policy tools

Typical first-generation innovation policy tools are funding and tax breaks for industry R&D and IPR protection, while second-generation tools encourage public-private partnerships of all kinds. Third-generation innovation policy instruments have yet to crystallise, but they appear to include living labs in which researchers, entrepreneurs, professionals, users, policymakers and/or the public co-create solutions to difficult societal problems in a real-life experimental environment.

3 Labs with differing aims, logic and added value

There is a lot of hype about living labs at the moment. All sorts of initiatives are calling themselves living labs, smart labs, field labs, and so on. From this proliferation of multifaceted labs, we can distill four basic types, each with their own aims, logic and added value. This classification can help politicians and policy makers to make the right decisions and choices in their innovation policy:

- The ‘Open Scientific Research Facility’ is a particularly suitable category for transferring knowledge from universities and research institutes to local industry. It fits in with a ‘knowledge valorisation’ policy.

- The ‘Field Lab for Manufacturing Industry’ category is especially appropriate for improving the innovativeness and competitiveness of enterprises by introducing them to new digital technologies. It is typical of modern industrial policy.

- The ‘Commercial Municipal Test Facility’ category allows entrepreneurs to test and refine prototypes of new products and services. Such facilities also help local communities promote themselves as a location or platform for innovation and serve as a tool for local economic policy.

- The ‘Living Lab’ category looks to be a suitable tool for learning about solutions and transition paths that address complex social problems. It fits in well with third-generation transformative innovation policy. It is, however,still too soon to tell whether living labs will live up to this promise. Much will depend on the way living labs are designed and used by local authoritiesLiving labs zijn momenteel onderdeel van een hype.

4 Proactive guidance of innovation by government

Innovation is not something that forces itself upon local authorities from the outside and to which they are obliged to adapt. Local authorities can also join local partiesin shaping innovation. Third-generation innovation policy requires a local government that actively seeks cooperation with other parties (other government agencies, industry, knowledge institutions, professionals, public initiatives, interest groups and/or civil society organisations), and that works with society to define the aims and direction of innovation. That also holds for living labs: if they are to contribute effectively to addressing societal challenges, the local authority must guide the experiments, in consultation with stakeholders.

For many public authorities, this broader, dialogue-driven approach marks a break with the recent past and with the current practice of entrusting matters to the market. Social innovation in new working methods and practices is crucial to harnessing technology for societal purposes. Living labs are ideally suited to combining social and technological innovation.

5 Living labs are more effective when municipal governments learn from one another

It is important for municipal governments to set up an active process in which they learn from one another and from other public authorities. A coordinated approach of this kind permits several different experiments to be conducted simultaneously and successively at different locations, making it possible to carry out similar experiments in different settings or different experiments in the same setting. It is a necessary step towards developing robust knowledge and solutions that can be applied in multiple locations. In short, each local living lab should make provision for cross-location learning.

6 Bear the ethical and societal aspects in mind

Experiments that are carried out in old-fashioned laboratories take place in the confined space of a building. In the living lab, however, they are conducted in public spaces. This means that people are part of the experiment, whether consciously or not. Experimentation requires openness, change and the sometimes flexible application of rules and laws.

But experiments are not necessarily positive and politically neutral in nature. Which experiments are being conducted? Who is participating in the experiments? How are we learning from their results, and who are we sharing those results with? Whether people benefit from the experiments, and how, depends on how we answer such questions. Experimentation must not lead to exclusion, remove protections, or expose participants to unacceptable risks. It is therefore important to establish ethical rules for responsible experimentation in living labs.

Read more:

Sources

[1] The Research and Development tax credit (WBSO) scheme, which the Ministry of Economic Affairs is using to encourage innovation by Dutch firms, is an example.

[2] Examples include the PPP allowance (part of the top sectors policy) and initiatives setting up regional clusters and ‘triple helix’ alliances.

[3] New technologies may breathe new life into manufacturing in the Netherlands or even lead to reshoring (bringing industry back to Europe from low-wage countries).

[4] This initiative won the European Enterprise Promotion Award in 2017.

[5] Many of these field labs are, in turn, associated with the national Smart Industry agenda.