Towards healthy data use for medical research

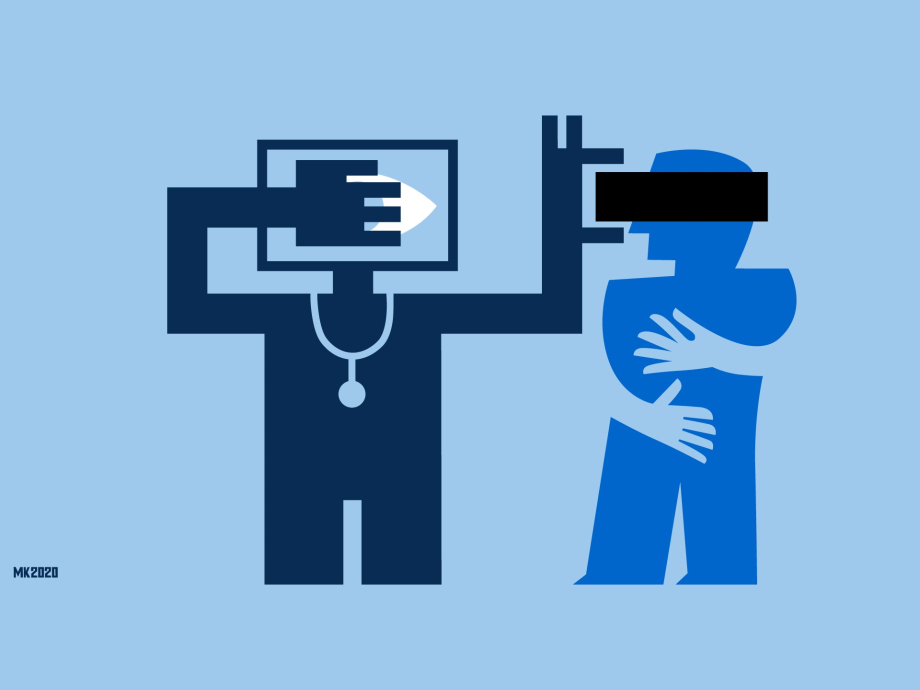

In the blog series 'Healthy Bytes' we investigate how artificial intelligence (AI) is used responsibly for our health. The use of AI is changing the practice of medical research. In this ninth part, lawyer Joost Gerritsen shows the legal questions that this change entails. What is healthy data use in the context of medical research?

In short

- How is AI used responsibly for our health? That's what this blog series is about.

- Lawyer Joost Gerritsen shows what legal questions arise now that medical researchers use AI applications that require a lot of patient data.

- These questions need to be debated so that it becomes clear what 'healthy data use' is in the age of AI in health care.

Looking for good examples of the application of artificial intelligence in healthcare, we asked key players in the field of health and welfare in the Netherlands about their experiences. In the coming weeks we will share these insights via our website. How do we make healthy choices now and in the future? How do we make sure we can make our own choices when possible? And do we understand in what way others take responsibility for our health where they need to? Even with the use of technology, our health should be central.

Medical data for research

The data in medical records may be useful for research. For example, for a comparative study between people with a desease and a healthy control group, in order to study risk factors for diseases. Sometimes this leads to life-saving insights.

The use of data from medical records is bound by legal rules. After all, patients are entitled to the protection of their privacy and their personal data. In practice, researchers often experience this protection of privacy as restrictive The legal rules are said to create unnecessary barriers to working with the data. Moreover, research practice is changing due to the deployment of new AI applications, which make use of large amounts of data. What are the rules and what are the legal challenges if patient data from medical records are used for research?

Rules for research with patient data from medical records

The Netherlands has specific rules for dealing with patient data. These are set out in the Medical Treatment Agreement Act (WGBO), as part of the Dutch Civil Code (Burgerlijk Wetboek). In addition, there is the General Data Protection Regulation (Algemene Verordening Gegevensbescherming or AVG), which contains general rules for the handling of personal data, such as health data about the patient.

The WGBO is applicable as soon as a patient and a healthcare provider enter into a treatment relationship. For example, if a patient receives personal advice from the GP or is being treated in hospital. A medical file is drawn up about the patient's treatment. This contains matters such as (health) information about the patient and information about the healthcare provider's operations.

The information in the file is protected by medical confidentiality. This means that the healthcare provider will not provide information about the patient to others without the consent of the patient (or their representative). The healthcare provider is also prohibited to give them access to the file - with exceptions such as the healthcare provider's replacement or a colleague involved in the treatment.

It follows from the WGBO that only in specific cases professional secrecy may be broken for purposes other than the primary purpose of treatment. An example of such a secondary (or additional) purpose is statistical or scientific research in the interest of public health. In that case, permission may be withheld if it is not reasonably possible or cannot be requested. Consider the situation that so many patients are participating in a study that it is practically impossible to ask all of them for permission. Or consider the situation in which asking for consent leads to a selective response and thus distorts the outcome of the study.

In addition, the study must safeguard the patient's privacy interests as much as possible. This can be achieved by not publishing information that can be traced back to the patient. The study must also serve the public interest. Furthermore, the data to be used must be necessary for the study. In addition, an objection facility must be set up so that the patient can object to the reuse of their data for research. Has the patient not had such a possibility or does he or she object? Then the data may not be used.

The question is how, in the age of AI, the balance should be made between research interests and the patient's privacy interests.

Legal challenges

Because of the WGBO, before the dossier data are legally suitable for research, necessary arrangements have to be made. But how do the rules relate to modern AI applications for healthcare and the opportunities offered by AI? For example, before a computer model can recognise breast cancer on mammograms (images of the mammary gland), many mammograms from numerous medical files must first be analysed. This is done automatically using AI, an algorithm.

In my opinion, it is not far-fetched to say that such an AI application can be used for public health research. The WGBO rules then apply. That need not be a problem, as long as all the requirements are met. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. For example, if the required possibility of objection has not been provided. Or because permission should have been requested but was not granted. Particularly with regard to older medical files, which may be distributed and dispersed among several health care providers, it is not always possible to check with certainty whether the WGBO rules on research have been correctly observed. In such cases, the data may not be examined by the algorithm. Do we think this is justified? Should the algorithm, and therefore the research, be forced to stop - despite the potentially life-saving impact?

What's next?

In the 1990s, with the WGBO, the legislator tried to strike the right balance between research interests and the patient's privacy interests. The question is how, almost thirty years later and in the age of AI, this balance should be made. And how does 'responsible use of data' fit in with this discussion, as the Rathenau Institute mentioned it in its Letter to the House of Representatives in October 2019? These are social questions. Let us therefore enter into debate with each other in order to examine what healthy, responsible, data use is in the age of AI in 2020.