Knowledge of the Future

A foresight study for science policy

Report

Downloads

This report describes how four major developments are changing the functioning of science and its relationship with society, posing challenges for science policy. These developments are: advancing digitalisation and artificial intelligence, increased direction in coordination and collaboration in the organisation of science, an increasing urgency of societal challenges, and changing international relations.

The exploration shows that more variety and new instruments in science policy are needed and provides tools for a dialogue about the future of science.

This report outlines four broad developments that affect the future of society in general and of science in particular. Together, they pose new challenges for science and science policy.

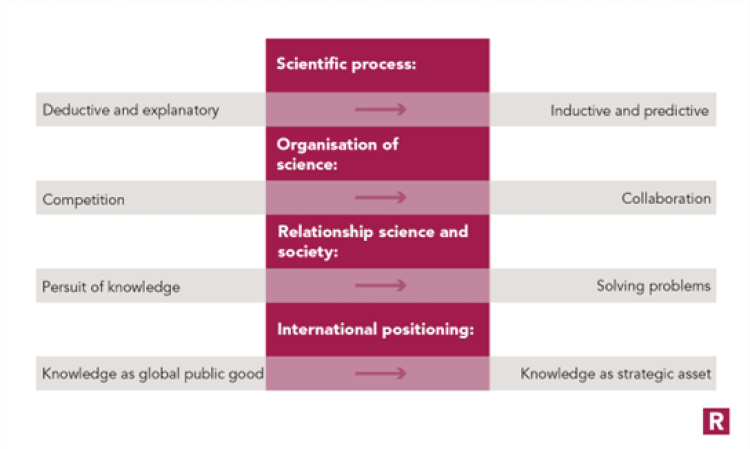

1. The scientific process

The main structural development that is radically changing scientific research is digitalisation. The use of digital technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI), can make research faster and more efficient and can create opportunities for new kinds of research. It is therefore not only the demand for ICT skills that is increasing in the research context, but also that for know-how about quantitative and statistical methods. At the same time, digitalisation may well lead to the private sector playing an increasing role in public research. Much of the necessary ICT know-how is concentrated, after all, in the big tech companies.

Further digitalisation of the scientific process will offer opportunities, but will also bring risks. For instance, the use of AI raises questions regarding the replicability and reliability of research results. The dominant position of big tech companies as regards ICT expertise and infrastructure calls for rethinking the relationship between the public and private sectors in the development of knowledge.

2. The way science is organised

In recent decades, the pursuit of excellence has increasingly become the central focus within academia. To promote excellence, knowledge institutions and funding bodies have given researchers ample scope to develop their research ideas freely and have relied heavily on competition to select the best ideas and to allocate research resources accordingly.

This hyper-competition has recently met with increasing resistance. An exclusive focus on research excellence comes at the expense of other valuable functions of scientific endeavour, including the valorisation of knowledge. Science policy is therefore increasingly moving more towards collaboration and societal impact. In the coming years, this will be reflected in new practices such as open science, the new system of 'recognition and rewards', and the promotion of team science and transdisciplinary research.

A key question is how science can be organised more around collaboration and less on the basis of competition for research resources. What will this mean as regards quality and efficiency? Another question concerns specialisation and the profiling of research institutions. Is this desirable, and if so, who should be responsible for it?

3. The relationship between science and society

Society is increasingly calling on science to provide solutions to pressing problems, ranging from climate change and pandemics to social tensions and economic inequality. The Dutch Government has therefore broadened the Top Sector Policy into ‘mission-driven top sectors and innovation policy’, focusing in part on societal goals. When assessing grant applications, the Dutch Research Council (NWO) requests an Impact Outlook or an Impact Plan. And because complex problems require the integration of knowledge from diverse disciplines and from actual practice, there is an increasing focus on interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaboration, for example in city labs, living labs, and academic workshops.

Greater public pressure on science to come up with solutions to pressing societal problems will reduce the distance between science on the one hand and politics and society on the other. This raises questions about what society should and should not expect from public knowledge institutions, about what is required in order to meet legitimate expectations, and about what needs to be done, where necessary, to safeguard the independence of science.

4. The international positioning of science

Scientific development has in recent decades taken place within an international framework; scientific knowledge is predominantly a ‘global public good’. Promoting open science will reinforce this shared nature of knowledge. But international relations are changing. A transition is taking place from a US-dominated to a more China-dominated world order. The question is what this means for how the global scientific community functions. The increasing focus on knowledge security suggests that much scientific knowledge is gradually being seen more as a strategic asset to be protected than as a communal asset.

Geopolitical tensions are leading to uncertainty. They prompt us to reflect on what constitutes strategic knowledge that our country must have at its own disposal, and which countries are reliable partners with which to jointly develop scientific know-how.

Challenges for the future

The four developments outlined in this report are likely to lead to fundamental changes and innovations in the way scientific research takes place, in the way science is organised, and in its relationship to society and to science in other countries. These changes will be more pronounced in some scientific fields than in others. On balance, this development is expected to bring about greater diversity in scientific practice, which calls for increased differentiation in policy instruments for guiding science in the right direction.

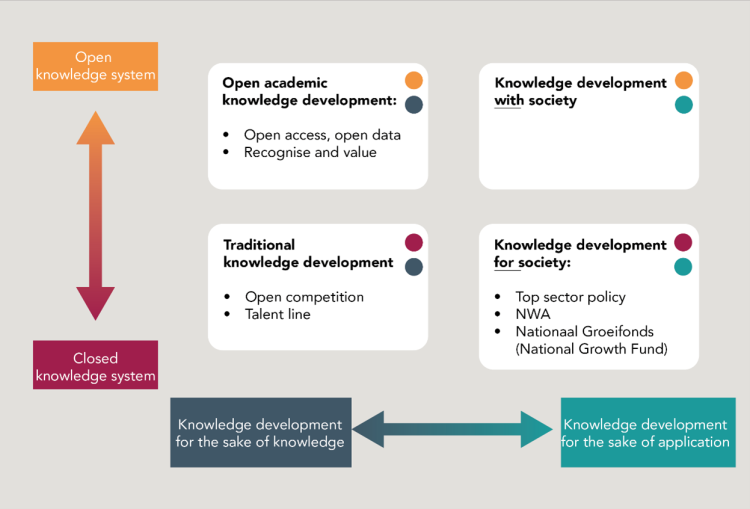

To characterise such diversity, we distinguish between policy instruments needed for a closed versus an open knowledge system. We also distinguish between instruments for knowledge development to expand the boundaries of knowledge versus instruments for generating knowledge for practical application. Whereas there is a great deal of experience with policy instruments for a kind of science that is relatively closed and that focuses on groundbreaking knowledge development, we still have only limited experience with instruments for an approach to science that is more open, interactive, and application-oriented.

The developments outlined in this report confront science and science policy with the need to make some important choices. Many of these involve finding a new balance, for example between the role of public institutions and private organisations in developing knowledge, between competition and collaboration in the allocation of resources, between fundamental research with a long-term perspective and knowledge development for tackling urgent short-term problems, between openness and knowledge security, and between conducting research for science, for society, and with society.

The purpose of this outline of influential developments is to extend an invitation to engage in an open dialogue about the science of the future and the future of science.