Politiek over leven

Debat over synthetische biologie

Rapport

Downloads

-

Het_Bericht_-_Synthetische_biologie_vereist_samenspraak.pdf

bestand type pdf - bestand formaat 214.81 kB

Download bericht aan parlement m.b.t.Politiek over leven -

Toekomstscenario's synthetische biologie

bestand type pdf - bestand formaat 1.09 MB

Download Toekomstscenario's synthetische biologie

Met Politiek over leven nodigt het Rathenau Instituut partijpolitieke en maatschappelijke organisaties uit om actief bij te dragen aan de publieke meningsvorming over synthetische biologie (biotechnologie). We gebruikten verschillende scenario's om het gesprek hierover aan te gaan.

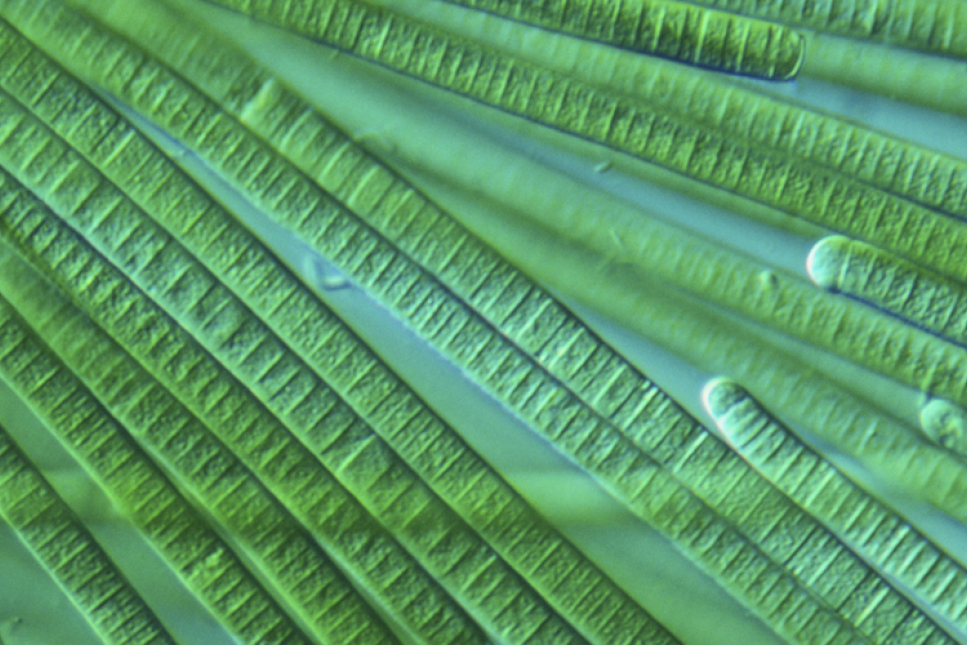

Een goedkoop malariamedicijn dat geproduceerd wordt door kunstmatige bacteriën, genetisch gemodificeerde superalgen die biobrandstoffen maken, het terugbrengen van uitgestorven diersoorten, of zelfs het creëren van kunstmatig leven. Synthetische biologie belooft een wereld aan mogelijkheden, maar waar willen we als samenleving naartoe met dit nieuwe wetenschapsgebied?

Vijf jaar nadat het Rathenau Instituut het rapport Leven maken publiceerde, maken we opnieuw de balans op. Van een politiek en maatschappelijk debat over synthetische biologie is het nog nauwelijks gekomen. Daarom organiseerde het Rathenau Instituut afgelopen jaar een Meeting of Young Minds: een debat tussen ‘synthetisch biologen van de toekomst’ en ‘Nederlandse politici van de toekomst’.

Het resultaat was een levendige en leerzame discussie waarvan we in deze publicatie verslag doen. Daarnaast geven we een overzicht van de laatste ontwikkelingen in de synthetische biologie en van omstreden maatschappelijke kwesties die dit boeiende nieuwe wetenschapsgebied heeft opgeroepen. Met Politiek over leven nodigt het Rathenau Instituut partijpolitieke en maatschappelijke organisaties uit om actief bij te dragen aan de publieke meningsvorming over synthetische biologie.

Bij voorkeur citeren als:

Rerimassie, V. & D. Stemerding: Politiek over leven. In debat over synthetische biologie. Den Haag, Rathenau Instituut 2012.

SynBio Scenarios

- SynBio Futures

We have listed a number of ‘vignettes’ presenting short stories of synbio futures (download: Toekomstscenario's Synthetische Biologie).

The stories describe possible futures for synthetic biology in our society and in our lifes. They are based on current developments in the field, but should not be read as predictions of the future. Our vignettes invite the reader to imagine and to consider ways in which synthetic biology might change our world, our ideas, values and ideals. We call them ‘techno-moral’ vignettes, because they explore both different fields of application for synthetic biology and the moral sensitivities and concerns that might be raised by these future synbio applications. See for a further explanation 'What are techno-moral vignettes?' down below.

We invite you to use the vignettes as a source for debate, starting with a few simple but important questions. What are exactly the issues raised in the vignette and what has changed in the world the vignette describes? What do you think of the issues described? Which person or argument in the story do you like most, or do you see as most controversial and why? Is this indeed a future in which you would like to live? What should be done in the situation the vignette describes and who do you see as most responsible? Is there a role for politics to play? We are really curious to know what you think!

2. What are techno-moral vignettes?

Well, they are certainly no predictions of the future, even though they do describe future events. If there is one lesson to be learned from the past, it is that the future cannot be predicted. Expect the unexpected – that is the slogan nowadays. Why then bother at all with trying to look ahead? The answer is simple: we cannot avoid to anticipate the future. Human beings constantly imagine the future, and then act on it. Indeed, why invest time and money – lots of money – in scientific or technological research, without the hope – or expectation – that this will somehow lead to a better world, one day?

The problem is that in the case of science and technology, we are not very good at anticipating the future. There are two types of claims scientists and engineers tend to make with regard to the future. The first is a very general claim: because science and technology are good things, they will somehow, someday, pay off. Society should therefore give a carte blanche to scientists and engineers and patiently wait for the results. The second type of claim is somewhat more specific: science and technology will provide the tools to solve problems like hunger, disease, climate change, energy scarcity. They help society to realize widely shared values: health, safety, sustainability, prosperity, etc.

The problem with the general claim is that we have learned that science and technology do not always produce good. And even if the promises are more specific, the claims often don’t come true. Technology does less as well as more than its makers had in mind. Cars were supposed to bring us from A to B really fast. But they have done much more: they have influenced how a country like the Netherlands is laid out, when and where people can still enjoy peace and quiet, they caused lung problems in children living near highways, they increased mobility and thus helped to reshape the cultural differences between city and village, and so on. And when everyone has a car, the original promise of getting really fast from A to B will not always be fulfilled, given the regular traffic jams.

As a rule of thumb, we can say that technologies in the future usually work out different from what the developers in the present hope and assume. New technologies are not like clay in our hands, but are really active agents: they help shape what we want, how we relate to each other, and how we relate to the world. If a really fast car is introduced on the market, there is a good chance that I now want to drive really fast, that my employer expects me to drive really fast (to work), and that I want the roads to be designed so that I can drive really fast. The invention of a really fast car may even motivate me to vote for a political party that allows me to drive really fast whenever and wherever I want.

Technology then is much more than a simple tool that helps us to realize what we want today. Therefore, it is our task to think ahead with a bit more creativity about what technology might bring. How will new technologies affect the way we live, the way we love, the way we hope, the way we demand rights? Only by asking questions like these we may seek a better understanding of the ways in which technology may contribute to a better world.

Vignettes are not predictions that close the debate, but invitations to everybody (including politicians and scientists) to come up with their own imagination of how science and technology may improve our lives. Will it help? Difficult to say. We know that technology development is usually a very large-scale and long-term enterprise, with many different parties involved, often in various parts of the world. So, it will not be easy. But ultimately, developments in science, technology, and society depend on choices made by humans, who are guided by better or worse reasons when choosing amongst different alternative ways of doing and making things. And because that is the case, it is always worth the effort to try to improve our reasons and arguments by discussing with one another.

3. About the authors

The SynBio Futures vignettes have been developed by a team guided by Tsjalling Swierstra from Maastricht University and Marianne Boenink from the University of Twente. First drafts of vignettes were made in classes of master students at both universities and then further developed and improved by Swierstra and Boenink. During the process the vignettes have been commented on by senior researchers involved in iGEM from VU University Amsterdam and Delft University of Technology, and by staff members from the Rathenau Instituut. The work has been commissioned by the Rathenau Instituut. The final authorship and responsibility for the vignettes rests with Tsjalling Swierstra and Marianne Boenink.

Authors involved from Maastricht University

Hanneke Berman

Patrick Berden

Maria Brückmann

Anika Haacke

Sven Schaepkens

Tsjalling Swierstra (project leader)

Authors involved from the University of Twente

Ellis Arkes

Lars Assen

Elena Chernovich

Lucie Dalibert

David Eckel

Tjebbe van Eemeren

Federica Lucivero

Judith Schoot Uiterkamp

Marianne Boenink (project leader)

Commenting team

Douwe Molenaar (VU University Amsterdam)

Domenico Bellomo (VU University Amsterdam)

Aljoscha Wahl (Delft University of Technology)

Virgil Rerimassie (Rathenau Instituut, The Hague)

Dirk Stemerding (Rathenau Instituut, The Hague)