China: a scientific superpower in the making

Exchanging knowledge is beneficial for a country like the Netherlands. Unsurprisingly,

international cooperation is one of the pillars of Dutch science policy. However,

international cooperation also involves risks. In recent years, the Netherlands and the

European Union have increased their focus on knowledge security. Previously, the Rathenau

Instituut emphasized the importance of conscious strategic international collaborations,

especially for scientists, institutions, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science. In

this way, we avoid becoming dependent on foreign funding and we can limit the risk of

external influences on research. Cooperation with researchers from undemocratic and

unfree countries is growing and geopolitical relations are shifting. To illustrate this, we will

look at the phenomenal size and growth of scientific research in China. We compare China with the US, the EU, and the Netherlands and look at the increasing cooperation between

Dutch and Chinese scientists.

In short

- China is catching up to and even overtaking the EU through impressive growth in R&D investments.

- Worldwide, China has the largest number of researchers and scientific publications and is growing faster than the EU, the US, and the Netherlands.

- With the rapidly growing cooperation of Dutch and Chinese researchers, informed and responsible choices are essential.

Phenomenal growth in Chinese R&D investments

Over the past 27 years, investments in research and development (R&D) in China have increased structurally and phenomenally (see Figure 1.1). Whereas in 1996, China was still at the same level as the Netherlands, since 2016, China's total R&D funding is higher than that of the 27 countries of the European Union together. The US is still the largest absolute investor in R&D during this entire period, but China is approaching the level of the US. Over the period 1996-2023, R&D expenditure in China grew the strongest by far: 3,829%, compared with 169% in the US and 116% in the Netherlands.

In the coming period, both the US and China plan to increase their investments in R&D. According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, the Chinese state will increase the R&D budget by 7% annually in the coming years (Shead, 2021; Normile, 2021). Both the US and China plan to invest mainly in research that focuses on technology (National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, 2021).

In addition, China shows a substantial structural increase in the total expenditure on R&D as a percentage of the GDP (see figure 1.2). With an increase from less 0.57% of the GDP in 1996 to 2.49% in 2023, China exceeds the Netherlands (2.23% in 2023) and the EU (2.13% in 2023). In addition, the tax benefit for companies to invest in R&D in China (0.07% of GDP in 2017) is lower than in the Netherlands (0.14% of GDP in 2018) and in the US (0.08% of GDP 2018).

At USD 651 in 2023, R&D investment per capita in China is still considerably lower than in the US, the Netherlands and EU countries (see Figure 1.3). Incidentally, China's population is also over four times larger than that of the US and three times larger than that of the EU (and over 80 times larger than that of the Netherlands). Here too, China shows the strongest growth. In 2023, for example, China invested over 56 times more in R&D per capita than in 1996. The other economies (US and EU) are showing solid growth for the same period, but not nearly as strong as China (about four times as much).

- Figure 1.1: Total R&D investment in millions of dollars (PPP)

- Figure 1.2: Total R&D expenditure as percentage of GDP

- Figure 1.3: R&D investment per capita

| Netherlands | China | EU-27 | United States | |

| 13.244,7 | 19.886,8 | 233.101,9 | 305.740,0 | |

| 1997 | 13.840,3 | 24.614,0 | 241.646,3 | 322.857,0 |

| 13.681,0 | 26.845,9 | 250.621,8 | 339.928,0 | |

| 1999 | 15.033,5 | 33.455,2 | 265.020,8 | 362.969,9 |

| 15.402,7 | 43.190,9 | 280.212,5 | 389.090,1 | |

| 2001 | 15.787,8 | 49.193,2 | 290.367,9 | 395.403,7 |

| 15.360,0 | 60.311,4 | 296.118,5 | 388.450,5 | |

| 2003 | 15.705,1 | 70.208,6 | 298.310,3 | 399.733,1 |

| 16.063,8 | 83.794,7 | 302.115,1 | 404.810,3 | |

| 2005 | 16.256,0 | 100.575,1 | 308.371,4 | 421.450,6 |

| 16.501,3 | 118.566,6 | 324.800,7 | 440.722,3 | |

| 2007 | 16.435,3 | 135.839,6 | 336.202,1 | 461.864,7 |

| 16.296,4 | 156.663,5 | 355.118,0 | 485.313,6 | |

| 2009 | 16.080,2 | 197.072,6 | 354.971,0 | 480.904,9 |

| 16.709,3 | 224.422,2 | 363.126,7 | 480.179,4 | |

| 2011 | 18.724,6 | 255.764,0 | 378.381,8 | 491.929,6 |

| 18.897,8 | 296.106,3 | 387.160,5 | 491.189,3 | |

| 2013 | 21.263,2 | 332.930,4 | 389.670,3 | 505.944,0 |

| 21.718,6 | 361.714,6 | 400.274,7 | 521.194,0 | |

| 2015 | 21.841,5 | 393.482,4 | 410.515,9 | 549.315,8 |

| 22.344,9 | 429.282,4 | 415.623,4 | 572.113,8 | |

| 2017 | 23.251,1 | 463.164,8 | 435.788,0 | 595.758,9 |

| 23.343,6 | 500.284,6 | 453.762,3 | 636.071,7 | |

| 2019 | 24.308,2 | 555.878,6 | 471.451,5 | 685.991,1 |

| 24.730,3 | 607.601,5 | 459.870,0 | 729.857,0 | |

| 2021 | 25.705,7 | 665.789,9 | 480.504,7 | 785.607,3 |

| 26.503,9 | 717.915,1 | 495.817,0 | 809.627,7 | |

| 2023 | 27.159,8 | 780.677,7 | 504.031,0 | 823.405,4 |

| Jaar | Netherlands | China | EU-27 | United States |

| 1,84 | 0,57 | 1,58 | 2,45 | |

| 1997 | 1,84 | 0,56 | 1,59 | 2,48 |

| 1,74 | 0,63 | 1,60 | 2,50 | |

| 1999 | 1,82 | 0,64 | 1,65 | 2,54 |

| 1,79 | 0,74 | 1,68 | 2,62 | |

| 2001 | 1,79 | 0,88 | 1,70 | 2,64 |

| 1,74 | 0,93 | 1,71 | 2,55 | |

| 2003 | 1,78 | 1,04 | 1,70 | 2,55 |

| 1,78 | 1,10 | 1,68 | 2,49 | |

| 2005 | 1,77 | 1,20 | 1,68 | 2,50 |

| 1,73 | 1,29 | 1,70 | 2,55 | |

| 2007 | 1,66 | 1,35 | 1,70 | 2,62 |

| 1,61 | 1,35 | 1,78 | 2,74 | |

| 2009 | 1,65 | 1,42 | 1,85 | 2,79 |

| 1,69 | 1,64 | 1,86 | 2,71 | |

| 2011 | 1,87 | 1,68 | 1,90 | 2,74 |

| 1,90 | 1,75 | 1,95 | 2,67 | |

| 2013 | 2,14 | 1,88 | 1,97 | 2,70 |

| 2,15 | 1,96 | 1,99 | 2,71 | |

| 2015 | 2,12 | 1,98 | 1,99 | 2,77 |

| 2,12 | 2,02 | 1,98 | 2,84 | |

| 2017 | 2,14 | 2,06 | 2,02 | 2,88 |

| 2,10 | 2,08 | 2,06 | 2,99 | |

| 2019 | 2,14 | 2,10 | 2,09 | 3,14 |

| 2,27 | 2,20 | 2,16 | 3,42 | |

| 2021 | 2,22 | 2,36 | 2,12 | 3,47 |

| 2,18 | 2,38 | 2,11 | 3,49 | |

| 2023 | 2,23 | 2,49 | 2,13 | 3,45 |

| Netherlands | China | EU-27 | United States | |

| 451,17 | 11,55 | 290,21 | 733,38 | |

| 1997 | 479,86 | 14,41 | 304,62 | 778,43 |

| 482,71 | 15,77 | 320,92 | 819,21 | |

| 1999 | 533,52 | 19,79 | 343,86 | 877,03 |

| 570,48 | 25,96 | 372,09 | 950,99 | |

| 2001 | 596,13 | 30,07 | 395,64 | 978,39 |

| 601,25 | 37,25 | 415,64 | 966,87 | |

| 2003 | 609,24 | 44,00 | 423,01 | 1.005,27 |

| 640,65 | 53,64 | 437,19 | 1.036,02 | |

| 2005 | 667,43 | 65,95 | 452,94 | 1.102,16 |

| 713,91 | 79,76 | 498,27 | 1.176,87 | |

| 2007 | 734,07 | 93,45 | 531,43 | 1.254,65 |

| 753,24 | 109,37 | 580,91 | 1.331,19 | |

| 2009 | 742,18 | 137,94 | 594,13 | 1.315,58 |

| 767,45 | 158,24 | 615,05 | 1.318,41 | |

| 2011 | 876,68 | 182,69 | 658,65 | 1.367,70 |

| 905,86 | 214,01 | 686,68 | 1.380,33 | |

| 2013 | 1.061,71 | 239,27 | 716,03 | 1.435,16 |

| 1.069,98 | 256,00 | 745,74 | 1.492,40 | |

| 2015 | 1.079,51 | 270,89 | 770,33 | 1.575,14 |

| 1.124,65 | 290,62 | 810,81 | 1.643,36 | |

| 2017 | 1.200,16 | 311,25 | 869,19 | 1.729,93 |

| 1.236,77 | 341,99 | 928,15 | 1.878,19 | |

| 2019 | 1.334,40 | 386,83 | 1.017,45 | 2.048,32 |

| 1.417,86 | 430,28 | 1.030,93 | 2.199,69 | |

| 2021 | 1.519,20 | 496,33 | 1.104,67 | 2.471,60 |

| 1.678,28 | 575,34 | 1.213,51 | 2.718,94 | |

| 2023 | 1.744,23 | 650,62 | 1.254,21 | 2.850,70 |

Limited international research funding

Across all economies, companies are the largest source of R&D funding (Figure 2.1). In China, companies made up 79% of total R&D investment in 2023. This number is for the US 70% and for the Netherlands and EU even slightly below 60%. This is partly due to the difference in economic structure. In China, the importance of the manufacturing industry in the economy (38%) is much greater than in the US (18%) and the Netherlands (17%), where the service sector, which is less R&D-intensive, plays a relatively larger role (see Figure 2.3).

In China, 18% of research funding comes from the government. Only a minor part comes from abroad (0.2%). In the other economies, in addition to companies, other stakeholders such as universities, private and non-private organisations and stakeholders from abroad play an important role. For example, 10% of Dutch R&D funding comes from abroad. It should be noted that in China, the division between public and private is less clear, which makes it less transparent which parties are behind Chinese financial flows. The Chinese state also exerts influence on companies through legislation and by making them partly state-owned (hybrid) (Witt & Redding, 2014; Hoffman & Kania, 2018). According to an independent advisory organisation to the Australian government (FIRB), hybrid ownership of companies (part state ownership) will become the norm in the Chinese market (Grigg,

2019).

Figure 2.2. also shows how R&D funding is divided by type of research. China and the US, for example, place a strong emphasis on experimental research. The Netherlands places relatively more emphasis on applied and fundamental research.

- Figure 2.1: R&D expenditure by source of finance (2023)

- Figure 2.2: R&D expenditure by type of research

- Figure 2.3: Share of manufacturing industry in economy (%), 2018

| International | Higher Education | Government | Corporations | |

| China | 0,17 | 17,77 | 79,02 | |

| United States | 6,15 | 5,21 | 18,94 | 69,7 |

| Netherlands | 10,22 | 2,44 | 29 | 58,34 |

| EU-27 | 9,88 | 2,35 | 30,75 | 57 |

| Fundamental research | Applied research | Experimental development | |

| China | 5,54% | 11,13% | 83,33% |

| United States | 16,64% | 19,82% | 63,54% |

| Netherlands | 25,75% | 42,31% | 31,94% |

| Share manufacturing industry of GDP (%) | |

| China | 39,6870118 |

| United States | 18,63860165 |

| Netherlands | 17,80572542 |

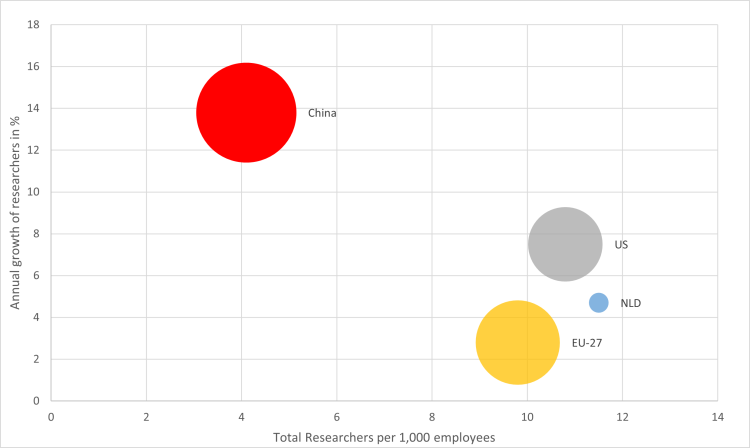

Largest number of researchers worldwide

China has the largest number of researchers worldwide. The growing investments in R&D have resulted in a strong increase in the number of researchers per 1,000 employees. Nevertheless, the number of researchers per 1,000 employees in China is still low. There is still potential for further growth. With more than ten researchers per 1,000 employees, the Netherlands is also ahead of the US and the EU. This is despite the relatively low percentage of GDP that the Netherlands allocates to R&D. The WBSO (promotion of research and development) may contribute to this. With this scheme, the Dutch government makes it fiscally attractive for companies to use its workforce for research (RVO). Fiscal measures to stimulate research have also recently been introduced and scaled up in many other countries, such as the US and China.

Image 1. Number and development of researchers in FTE.

China overtakes US in scientific output

The development of China as a new scientific world power is also reflected in its increase in scientific publications (see Figure 3). These are English publications listed in the Web of Science database of Clarivate Analytics. China's strong upward trend since 2011 came to a head in 2019, when, for the first time, China produced the largest number of scientific publications worldwide. The other reference countries also show an increase, but nowhere near the level of China. Up to and including 2018, the USA still produced the largest number of scientific publications worldwide. Between 2011 and 2023, the number of publications in the US grew a lot less (16%) than in China (350%) - yet another way in which China surpassed the US. In the Netherlands, the number of scientific publications grew by 42%. After 2021, all reference countries except China show a slight decrease in the number of publications per year.

| United States | China | United Kingdom | Germany | Japan | France | Netherlands | |

| 2011 | 364624 | 162199 | 100372 | 95397 | 77466 | 67459 | 33777 |

| 2012 | 377398 | 188024 | 105130 | 100087 | 78252 | 69856 | 36471 |

| 2013 | 392076 | 221879 | 111687 | 104085 | 79902 | 72854 | 38397 |

| 2014 | 399827 | 256227 | 112074 | 105376 | 78439 | 72946 | 39049 |

| 2015 | 408453 | 287459 | 118706 | 108584 | 78079 | 75439 | 40273 |

| 2016 | 422763 | 317292 | 126397 | 113563 | 80798 | 78698 | 42460 |

| 2017 | 434144 | 353938 | 131703 | 117266 | 83091 | 79976 | 43457 |

| 2018 | 446041 | 407138 | 137814 | 120067 | 85074 | 80344 | 45407 |

| 2019 | 455007 | 478715 | 142272 | 123991 | 86170 | 81440 | 47031 |

| 2020 | 477076 | 540474 | 152013 | 131138 | 93267 | 86928 | 49835 |

| 2021 | 495368 | 607098 | 163683 | 143209 | 99173 | 90487 | 53974 |

| 2022 | 459628 | 730243 | 152994 | 133543 | 93043 | 84207 | 50812 |

| 2023 | 423543 | 730583 | 142344 | 124203 | 85111 | 78553 | 47978 |

Output growth is above average in all domains

The impressive increase in the number of Chinese publications is visible in every field of science (Figure 4). At 1,607%, the percentage increase is strongest in agricultural sciences. Across disciplines, we see that China gives a boost to the average publication increase of the reference countries. This effect is greatest in engineering and least in social sciences.

| % increas scientific publications NLD | % increase scientific publications China | % increase scientific publications, reference countries | % increase scientific publications reference countries, without China | |

| Agriculture | 56 | 1607 | 115 | 60 |

| Engineering Sciences | 128 | 1077 | 230 | 113 |

| Health Sciences | 130 | 1496 | 136 | 101 |

| Natural Sciences | 95 | 576 | 122 | 73 |

| Social Sciences | 237 | 1664 | 213 | 183 |

Citation impact reaches world average

Figure 5 shows that, in terms of citation impact score (an indicator of scientific quality and relevance), China exhibits the strongest development of all the reference countries. In the period 2006-2022, the citation impact score of Chinese science grew from 0.71 to 1.02. In terms of citation impact, in 2022, China is just above the world average. The Netherlands is among the world leaders, just below Singapore, the United Kingdom and Switzerland.

| 2003-2006 | 2019-2022 | |

| SGP | 1,03 | 1,37 |

| UK | 1,24 | 1,31 |

| CHE | 1,33 | 1,30 |

| NLD | 1,28 | 1,28 |

| USA | 1,35 | 1,19 |

| AUS | 1,07 | 1,18 |

| DNK | 1,24 | 1,16 |

| IRE | 1,01 | 1,16 |

| BEL | 1,11 | 1,12 |

| SWE | 1,11 | 1,12 |

| CAN | 1,12 | 1,09 |

| NOR | 1,13 | 1,09 |

| AUT | 1,04 | 1,08 |

| FIN | 1,05 | 1,07 |

| ITA | 0,94 | 1,06 |

| DEU | 1,06 | 1,04 |

| CHN | 0,71 | 1,02 |

| FRA | 1,02 | 1,01 |

| ESP | 0,93 | 0,94 |

| KOR | 0,74 | 0,82 |

| JPN | 0,75 | 0,71 |

Our factsheet on the 'Development of the scientific research profile of the Netherlands' shows that, in every scientific domain except Engineering, the Netherlands is in the Top 5 with regards to citation impact. This is not the case for China, despite its astronomical growth. There are, however, three disciplines where China surpasses the Netherlands in terms of citation impact: economics (China on 2, NL on 7), instrumentation sciences (China on 6, NL on 9) and Statistics (China on 6, NL on 9). According to the China report of the European Commission, China mainly wants to grow in technological scientific disciplines such as: new generation IT, high-end numerical control machinery, and aerospace engineering. By investing in this, the Chinese government wants to acquire a more dominant position within the technological science domain, and make itself less dependent on other countries (Alves Dias et al., 2019).

International cooperation in China still underdeveloped

Looking at developments in the number of international co-publications as a percentage of the total number of publications, we see an increase for all reference countries (Figure 6). In the Netherlands, the share of co-publications increased from 55% in 2009-2012 to 70% in 2019-2022. In China, the share of international co-publications is the lowest of the reference countries at 25% in 2017-2020. Since 2010, China's share of international publications has increased by less than one percentage point.

| 2009-2012 | 2019-2022 | |

| CHE | 66,14% | 77,32% |

| SGP | 54,70% | 75,30% |

| BEL | 61,10% | 75,00% |

| AUT | 62,94% | 74,48% |

| SWE | 58,28% | 72,22% |

| DNK | 58,99% | 71,94% |

| NOR | 56,55% | 71,09% |

| IRE | 54,04% | 70,54% |

| FIN | 54,33% | 70,36% |

| NLD | 54,95% | 69,52% |

| UK | 49,93% | 68,53% |

| FRA | 51,93% | 65,00% |

| AUS | 46,80% | 64,89% |

| CAN | 46,85% | 61,81% |

| DEU | 50,23% | 61,23% |

| ESP | 44,12% | 56,61% |

| ITA | 44,34% | 54,36% |

| US | 31,48% | 43,70% |

| JPN | 26,94% | 36,54% |

| KOR | 27,55% | 34,04% |

| CHN | 24,09% | 24,68% |

Number of Dutch-Chinese co-publications quadrupled

The figure below shows that the number of Dutch-Chinese co-publications has increased by 400% in the past decade: from 894 in 2010 to 4,459 in 2020. The three domains in which the Netherlands and China collaborated the most in 2020 are: environmental sciences (411 co-publications in 2020), multidisciplinary materials sciences (333 co-publications) and astronomy and astrophysics (272 co-publications).

| NLD-CHI co-publicaties | |

| 2010 | 894 |

| 2011 | 1089 |

| 2012 | 1444 |

| 2013 | 1491 |

| 2014 | 1784 |

| 2015 | 2082 |

| 2016 | 2562 |

| 2017 | 2895 |

| 2018 | 3324 |

| 2019 | 4166 |

| 2020 | 4466 |

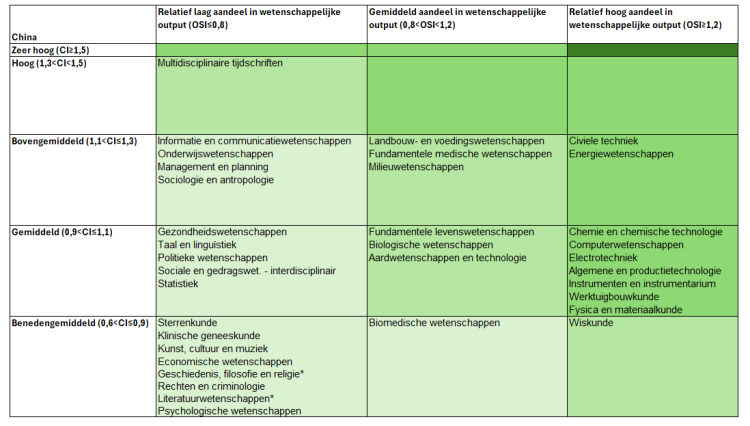

Specialisatiegraad en citatie-impact per wetenschapsgebied, 2019-2022

China’s wetenschappelijke productie laat een wisselend beeld zien (zie onderstaande tabel). In technisch georiënteerde vakgebieden zoals computerwetenschappen, elektrotechniek, civiele techniek, chemische technologie en energiewetenschappen heeft China zowel een relatief hoog aandeel in de wetenschappelijke output als een gemiddelde tot bovengemiddelde citatie-impact. Ook in verschillende natuur- en levenswetenschappelijke domeinen, waaronder de fundamentele medische wetenschappen, fundamentele levenswetenschappen, biologische wetenschappen en aardwetenschappen is de citatie-impact gemiddeld tot bovengemiddeld, terwijl het aandeel in de output daar meer in de middenmoot ligt.

Andere vakgebieden, zoals klinische geneeskunde, kunst en cultuur, economische wetenschappen, geschiedenis, filosofie en religie, rechten en criminologie, literatuurwetenschappen en psychologische wetenschappen, laten juist een relatief laag aandeel in de output zien. In deze disciplines varieert de citatie-impact van benedengemiddeld tot gemiddeld. Dit geheel maakt duidelijk dat China breed vertegenwoordigd is in uiteenlopende onderzoeksgebieden, maar dat het relatieve aandeel en de citatie-impact per vakgebied sterk verschillen.

Notities: * Deze gebieden behoren tot de Geesteswetenschappen. Evenals Rechten zijn de Geesteswetenschappen niet goed vertegenwoordigd in Web of Science, aangezien het in deze velden gebruikelijk is om ook op andere wijzen te publiceren.

In conclusion

The phenomenal growth and the unparalleled manpower in Chinese science results in the largest and strongest growing number of scientific publications worldwide. The Chinese state plans to stimulate

this growth in R&D even further. For example, there are plans to increase R&D investments by 7% annually over the next five years. The largest consumer of this increased research budget will be the

technology sector.

Scientific quality, measured by citation impact, is also improving significantly. However, there is still more to be gained for China in this area. International scientific cooperation can play an important role

here, from which both Chinese and Dutch scientists can benefit. The rise of China as a scientific superpower can offer opportunities for scientific cooperation and for solving global issues. But

scientific cooperation also involves risks. This certainly applies to cooperation with researchers from countries such as China, which score low on the Democracy Index and the Freedom Index (Economist

Intelligence Unit, 2020; Vasques & McMahon, 2020).

While decentralisation seems to be taking off in China, some sectors, including science, are still centrally governed with a high dependence on state policy and state control (Benner, 2018, Kirby & Van

der Wende, 2019). The sources of funding for Chinese science are less diverse than those in the Netherlands and the other reference countries. Funding from abroad and by private non-profit

organisations does not seem to play a significant role. Although companies are the largest financiers of Chinese science, there are indications that the Chinese state also exerts influence through this channel. While the number of state-owned companies is decreasing, the number of hybrid companies (mixture of private and state ownership) is increasing. The dominant presence of the Chinese government within science can lead to undesirable influence and there are indications that members of the Communist Party of China are entering (international) science as researchers to serve the interests of

the party (Joske, 2018).

In the Bericht aan het parlement on knowledge security in higher education and science, the Rathenau Instituut already indicated that international cooperation and international mobility of scientists are of great importance to the Dutch knowledge economy. At the same time, there must be sufficient awareness of the risks involved at all levels: for the individual researcher, for research institutions and for the Netherlands as a whole. In earlier research, the Rathenau Instituut described examples of such risks. These include knowledge that can be used for both civil and military purposes (dual use) or risks in the field of economic interests (intellectual property) and ethics (human rights) (Rathenau Instituut, 2019). In the Message to Parliament, we shared several insights and suggestions for ensuring knowledge security in international cooperation.

The European Commission sets conditions for so-called 'third' countries to participate in the new Horizon Europe research programme. Non-EU and EEA countries must:

• have high qualifications in science, technology and innovation;

• commit to a rule-based, open market economy, including a fair and equitable approach to intellectual property rights and respect for human rights, supported by democratic institutions;

and

• promote active policies to improve the economic and social well-being of citizens.

(EU regulation on Horizon Europe, adopted 28 April 2021: Article 16).

Sources

Alves Dias, P. et al. China: Challenges and Prospects from an Industrial and Innovation Powerhouse, Preziosi, N., Fako, P., Hristov, H., Jonkers, K. and Goenaga Beldarrain, X. editor(s), EUR 29737 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019, ISBN 978-92-76-02998-4, doi:10.2760/572175, JRC116516.

Benner, 2018. New Global Politics of Science: Knowledge Markets and the State. Edward Elgar Publishing – p. 33 https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/publication/1c5a4179-29b2-4e97-9196-28511a8f13b9

EU-verordening over Horizon Europe, vastgesteld 28 april 2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/NL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R0695&from=EN

Grigg, A. (2019, 16 januari). No such thing as a private company in China: FIRB. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/policy/foreign-affairs/no-such-thing-as-a-private-company-in-china-firb-20190116-h1a4ut

Hoffman, S., & Kania, E. (2018, 13 september). Huawei and the ambiguity of China’s intelligence and counter-espionage laws. Australian Strategic Policy Institute - The Strategist. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/huawei-and-the-ambiguity-of-chinas-intelligence-and-counter-espionage-laws/

Joske, A. (2018, oktober). Picking flowers, making honey - The Chinese military’s collaboration with foreign universities (Nr. 10). The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2018. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/picking-flowers-making-honey

Kirby & Van der Wende, 2019. The New Silk Road: implications for higher education in China and the West? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 12, nr.1. p. 127-144. See p.140 https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy034

National Security Comission on Artificial Intelligence. (2021, maart). Final Report - National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. https://www.nscai.gov/2021-final-report/

Normile, D. (2021, 5 maart). China announces major boost for R&D, but plan lacks ambitious climate. Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/03/china-announces-major-boost-rd-plan-lacks-ambitious-climate-targets

Politico (2021, maart) https://www.politico.eu/article/commission-plans-to-limit-research-tie-ups-with-china/

Rathenau Instituut (2020). Balans van de wetenschap 2020. https://www.rathenau.nl/nl/vitale-kennisecosystemen/balans-van-de-wetenschap-2020

Rathenau Instituut (2019). Kennis in het vizier – De gevolgen van de digitale wapenwedloop voor de publieke kennisinfrastructuur. Den Haag: Rathenau Instituut. https://www.rathenau.nl/nl/vitale-kennisecosystemen/kennis-het-vizier

Rijksoverheid (BuZa). (2021). China kennisnetwerk Rijksoverheid [verslag online seminar].

Shead, S. (2021, 1 maart). China’s spending on research and development hits a record $378 billion. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/01/chinas-spending-on-rd-hits-a-record-378-billion.html

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2021). Democracy Index 2020 - In sickness and in health? https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/

Vásquez, I., & McMahon, F. (2020). Human Freedom Index - A Global Measurement of Personal, Civil and Economic Freedom. Cato Institute & Fraser Institute. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/2021-03/human-freedom-index-2020.pdf

Witt & Redding, 2014, China: authoritarian capitalism. Chapter 2 in: the Oxford Handbook of Asian Business Systems - https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2171651 – p.4